French Soldiers on Parade, 1939

Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, and, true to their treaty obligations, Britain and France declared war on Germany. However, neither nation did much to help their Polish ally. With the Germany army heavily engaged in Poland, the French could have launched an attack from the east. Instead, the French high command remained totally wedded to its defensive strategy. The Poles fought valiantly, but by the end of September the country was virtually out of the war and divided between occupying forces from Germany and the Soviet Union. This division was in accordance with a secret clause in the German-Soviet non-aggression pact. The Germans then began transferring their troops to the western front, and Hitler urged his generals to rush preparations for an attack on France. For various reasons, however, the attack was delayed until May 1940.

For seven months following the fall of Poland there was a period known to journalists as the sitzkreig or Phony War. The Germans and Allies stared at each other across no-man’s land. Hitler made some peace overtures, but the Allies would not accept so long as Poland was occupied. And why should they trust Hitler to keep any promises? Therefore, the British and French simply awaited developments and tried to prepare for an expected onslaught.

While waiting, the Allies engaged in a very timorous sort of warfare. A few bombing raids were conducted against German military installations, and there were some limited naval operations, but otherwise things remained quiet. In fear of reprisals, British bombers dropped propaganda leaflets on German cities rather than bombs. The Luftwaffe had acquired a fearsome reputation, and residents of London and Paris were very concerned about the possibility of German bombing raids. In truth, neither Briton nor Frenchman had his heart in this war.

In April 1940, the Germans surprised the Allies with a quick strike north at Denmark and Norway. The Allies attempted to respond but were generally unsuccessful. Denmark was overwhelmed in a matter of hours, and the Norwegian campaign ended in early June 1940 with that nation’s complete occupation.

On May 10, 1940, the Germans finally attacked in the west. The sudden and complete collapse of France that followed was a shock to the entire world. German victory was not that unpredictable, but the speed and totality of it was a surprise to everyone, including the Germans. It remains an irradicable stain on French arms.

When the war began in September 1939 the French Army was believed by many to be the best in the world. Germany had a far stronger air force, but wars still must be fought out on the ground, and many observers thought the French might have an advantage in that area. France also had the Maginot Line, a massive series of fortifications along the French-German boundary.

Marshal Maurice Gamelin, who had achieved some distinction as a French staff officer in World War I, was serving as the overall Allied military leader, and he had developed detailed plans to be put into operation once the Germans resumed their offense in the spring of 1940.

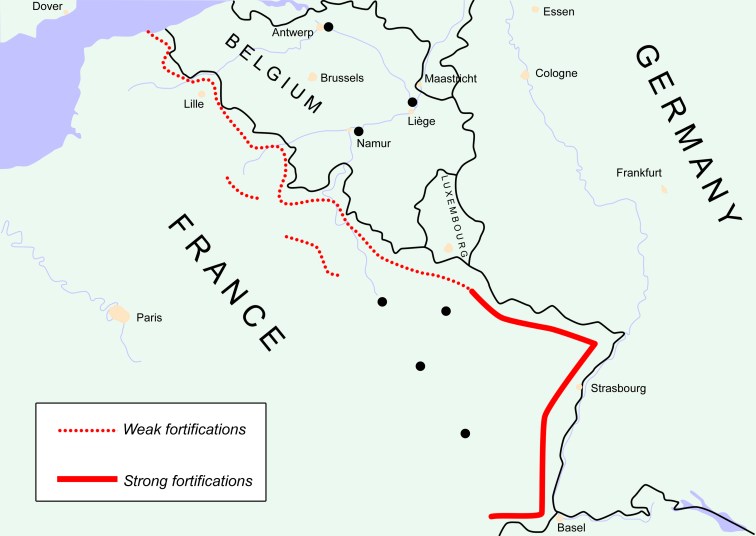

No one could be certain where the enemy would strike, but Gamelin was convinced that the Maginot Line would effectively deter any German assault along the Franco-German border. Marshal Gamelin’s confidence in the line was not misplaced. In the years since World War 2 there has been a tendency to disparage fixed fortifications, but the Maginot Line was truly impressive. Heavy, well protected guns had been sited to give covering fire to other strongpoints, and infantry units were placed behind the line for counterattacks in the event the enemy attempted a penetration in force. Unfortunately, Gamelin deployed a full 45 French infantry divisions in support of the Maginot Line, an excessive number considering the strength of the fortifications. Only 14 German divisions were facing them; and, as things developed, the Germans never made any serious attack in this area until the battle was virtually over and supporting infantry had been withdrawn. Another 9 French divisions were stationed along the Franco-Italian border. That number proved to be more than adequate when the Italians entered the war and attacked France on June 10. The French threw them back with no difficulty, but by then the war had been lost.

The Maginot Line

With the Franco-German and Franco-Italian borders secure, Gamelin expected that the Germans would charge at France through Belgium much as they had done in 1914. This time German offensive plans also involved the Netherlands, but that had little impact on the overall campaign.

French fortifications were much less formidable along the Belgian and Luxembourg borders north of the Maginot Line. This area was not suited for deep fortifications; but more to the point, Gamelin’s plans called for Allied units to advance and confront the Germans in central Belgium and prevent their incursion into France. The German army had occupied and devastated northeastern France during World War I, and the French were determined to avoid a repeat.

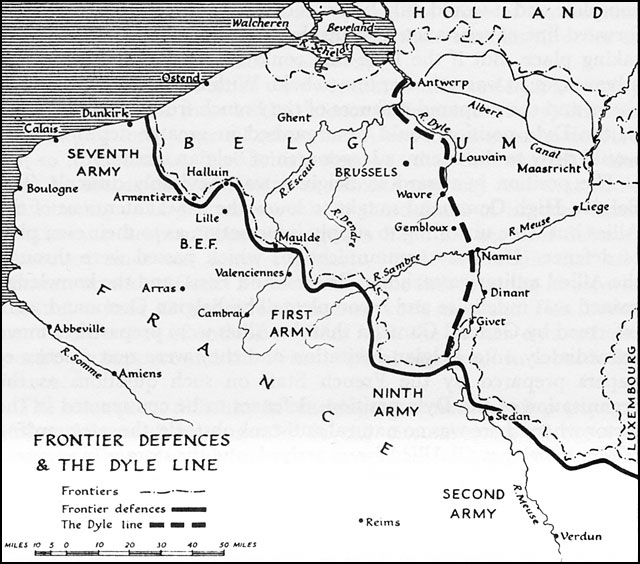

By tapping its manpower resources to the fullest, France managed to field 109 army divisions. With 54 French divisions deployed along the German and Italian borders, 55 were available for the decisive struggle in the north. Only 21 of these French divisions deployed in the main battle area were well-equipped, first-class fighting units, another 13 were second class reserve divisions of mixed quality and 21 divisions composed the general reserve (older reservists). Alongside the French were the 11 first-class divisions of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and 20 Belgian divisions. The Dutch could field 10 divisions, but they were poorly equipped and out of the fight within a few days. Facing the Allied troops in the north would be the 135 divisions of the Wehrmacht, minus those 14 divisions along the Franco-German border. This gave the Germans a 121 to 86 divisional advantage in the critical zone. Perhaps 36 of the German divisions could be considered fully equipped, first-class units, another 40 second class, and 45 were in their general reserve. The allies would be outnumbered in this area, but these were not impossible odds for soldiers in strong defensive positions. The moment German forces violated the Dutch and Belgian frontiers, Gamelin planned to send his strongest and most mobile formations forward to take up defensive positions along the Dyle River in central Belgium. He was confident that French troops, allied with the British and Belgians, could hold off the German onslaught on that narrow front.

The Dyle Line

Along with the Germans, the French had the most experienced and battle-ready troops on the continent, and overall the French were probably better equipped. Many senior officers and NCOs in both armies had served in the Great War and were tactically proficient. The British Expeditionary Force consisted of more than 350,000 men It was well trained and led, but it was a small force when compared to the size of the French and German armies; and this was even though the United Kingdom’s population was slightly larger than that of France in 1940. The British were slow to realize that they were in a life-or-death struggle. The 20 division Belgian army consisted of a few first-class fighting units along with reserve formations of questionable quality.

The greatest German advantage was in their offensive spirit, which was enhanced among frontline soldiers by the heavy use of methamphetamines. The German military pioneered the use of performance enhancing drugs. Also, they developed a new battlefield tactic that involved combining large armored formations with infantry and air support to achieve breakthroughs. The Germans had valuable practice with these tactics in Poland.

The French had more tanks than the Germans, but they were widely dispersed among infantry units in a support role. At the urging of armor enthusiasts like Charles De Gaulle, the French had formed four armored divisions, but they were only recently organized and entirely untested. The ten German panzer divisions had been bloodied in the Polish campaign. Therefore, as the new battle began on the western front the Germans had a significant edge over the French and British in organizational structure and in their appreciation for the effect of fast-moving tank formations supported by infantry and combined with incessant air attacks. This new tactic was referred to by journalists as blitzkrieg or lightening war.

Following the German charge into Holland and Belgium on May 10, the French and British units along the Belgian border moved north to link arms with their new allies. There had been no military pre-planning with the Belgians. Belgium had scrupulously maintained a posture of neutrality and did not wish to give Hitler any excuse to draw them into the war. Of course, Hitler needed no excuse, and because of the lack of coordination, there was considerable confusion as British and French troops moved into position alongside the Belgians on the Dyle. The German juggernaut quickly charged through the Netherlands and northern Belgium and struck the Allies before they had a chance to fully deploy.

As the battle began the Allied and German forces were situated as follows. The BEF (11 divisions), French 1st Army (10 divisions), and French 7th Army (7 divisions) were moving north to join the Belgians. The 7th even raced into the Netherlands to help the Dutch, but the Dutch quickly capitulated, and the 7th retired south toward the Dyle. Holland’s rapid exit from the war was prompted by the German air force’s massive bombing of Rotterdam and threats of more such raids to come. There were heavy civilian casualties, and the Dutch ran up the white flag to avoid more useless slaughter.

Meanwhile, the German 6th Army (19 divisions) and 18th Army (11 divisions) had charged southeast to attack the Allies in Belgium.

Gamelin positioned the French 9th Army (9 divisions) and the French 2nd Army (8 divisions) to the right of the BEF and French 1st Army on the Dyle. The purpose of these other armies was to protect the 1st Army’s flank and provide a link to units along the Maginot Line. The southernmost units of the 9th Army and all divisions of the 2nd were situated to the immediate west and south of the Ardennes, a heavily forested area of southeastern Belgium that the French commander believed to be entirely unsuited for mechanized operations. Gamelin knew that the Germans might send infantry through the Ardennes, but he believed the passage of major armored units and heavy artillery through that difficult terrain was practically impossible. He sent no major French units into the Ardennes, and units assigned to the 9th and 2nd Armies and posted on the edges of the forest were chosen based on his conviction that it was extremely unlikely they would become heavily engaged in the fighting. A number of these divisions were reservist organizations of questionable quality and poorly equipped with antiaircraft and anti-tank guns. Gamelin assumed that if these troops should come under heavy attack by German infantry, reinforcements could be moved up in time to provide necessary support.

By May 12th Allied and German forces were fully engaged in central Belgium along the Dyle River line. The results were mixed. The Germans were the aggressors, but the Allies were holding their own. In fact, French tanks performed better than German armor in the Battle of Hannut, and Allied troops repulsed German infantry attacks all along the front. All seemed to be going as Gamelin had planned. The next day, however, a mailed fist struck French armies on their right.

Large German units, including armored formations, managed to rapidly push their way through the Belgian Ardennes area virtually uncontested, and on May 13th they confronted elements of the 2nd and 9th French Armies along the Meuse River. The speed of the attack was jaw-dropping. High on methamphetamines, German tank drivers covered ground night and day,

Breakthrough

almost without stopping. French commanders were caught entirely off guard and failed to respond with the necessary alacrity. The French regular units fought well, but the poorly prepared reservist divisions were extremely vulnerable. Woefully underequipped with anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns, one or two of these divisions broke under the attacks of German armor and infantry combined with relentless bombing by German aircraft. German air support took the role of heavy artillery. The fearsome Stuka dive bombers were particularly effective against unprotected infantry. A hole was punched in the French line, and German tank units raced toward the French coast

The German left wing now swinging into northern France comprised the bulk of the German Army’s offensive power. It consisted of the 4th, 12th, and 16th German Armies plus Panzer Groups Kleist and Guderian, a total of 46 divisions, including 9 panzer (tank) divisions. The Germans had another 45 divisions, lower quality units, in their general reserve.

On May 15th the rapidly advancing German left faced the remnants of the French 2nd and 9th Armies along with French reserve formations totaling another 21 divisions. These reserve units were badly situated, mostly unmotorized, and unable to respond quickly to the growing crisis.

Winston Churchill had succeeded Chamberlain as British Prime Minister on May 10th, the very first day of the German offensive. On May 15th Premier Reynaud contacted Churchill and told him that the battle was lost. The news seemed unbelievable. The British leader flew to Paris on May 16th and pressed Marshal Gamelin for a counterattack, but Gamelin informed him that he had no mobile reserve. Churchill was shocked by this statement as well as the general air of defeatism that seemed to infect the French high command. Almost all French mobile formations had been rushed into Belgium on the first day of battle, and they were now in danger of being cut off in the north. The only remedy was to attempt a breakout and try to regroup.

Marshal Gamelin was dismissed on May 19th and succeeded by General Maxime Weygand, a capable commander; but the change in command did not immediately improve the overall situation. Weygand had to be recalled from Syria, and the inevitable delays arising from switching generals disrupted Allied plans for a counteroffensive and breakout. Two or three critical days were lost during the change of leaders, and in the meantime the situation had become even more difficult.

On May 20th German armored units reached the English Channel, severing supply lines to the Allied armies in Belgium, more than a million men. These armies contained the best and most mobile British and French formations. They continued to fight the Germans to their north and east while facing increasing pressure from the south. With lines of communication completely severed, the Allied units began to experience shortages of food and supplies, including essential ammunition and fuel. There were several abortive attempts to break the encirclement, but all failed. The Belgians fought alongside the British and French until surrendering on May 28th. The situation was desperate for the remaining Allied forces, and they had already begun retiring toward the Channel ports in hope of evacuation. Then came the Miracle of Dunkirk. Over the period May 27 through June 3 over 339,000 British and French troops were transported from Dunkirk to Britain, saving them from certain destruction or capitulation. All their tanks, artillery, and trucks were abandoned along with perhaps 700,000 Allied prisoners of war (Brench, British, and Belgian) from various parts of the collapsing front. Some British and French units fought courageously and brilliantly in defense of the Dunkirk perimeter, but the overall campaign could only be labeled as a total Allied disaster.

Dunkirk

The Germans then regrouped their armies in northern France for the final thrust. They now had far better than a two-to-one divisional advantage, and the French had lost almost all their mobile armored units. The outcome was not long in doubt. Weygand organized the defense skillfully, and the French fought desperately. Within a few days, however, panzer units managed to bypass French strong points and break into open country. On June 10th Italy joined the war on Germany’s side, declaring war against both France and Britain. On June 14th the Germans entered Paris. On June 22nd the French surrendered.

Following World War II there has been a tendency to criticize the French for their rapid collapse and to disparage the quality and bravery of French fighting men. Indeed, the French military has become the butt of jokes.

Certainly, the French decision to surrender on June 22nd, 1940, can be censured. France and Britain had promised each other not to make a separate peace. After the collapse in the north, Paul Renaud, Charles de Gaulle and some others wished to continue the war from North Africa, but the defeatists took charge and sued for an end to hostilities. It was not France’s finest hour, and the new French government was little more than a lackey to its German masters, bringing even more shame to the French nation.

As France surrendered, there were some British leaders who also wished to negotiate with Hitler, but Churchill stood firm. At this critical moment in its history France needed a leader with the stature and grit of a Churchill. Unfortunately, no such man was available. De Gaulle had the grit but not the stature. He was only a colonel when the war began.

Several military historians have stated that the French army’s fate was determined before the battle began because of Gamelin’s foolish troop dispositions. Prior to the battle he should have moved many of the divisions backing the Maginot Line north to the critical front; and the French 7th Army, instead of racing into Holland, would have been much better employed as support for the Belgian, British and French armies on the Dyle. As for the Ardennes, a few well equipped divisions might have been rushed into that area and blocked the German thrust through that difficult and highly defensible terrain. Instead, despite intelligence warnings, Gamelin assumed the Germans could not move armor through such a heavily forested area and sent no troops to prevent such a passage. This proves the old adage that “assumption is the mother of foul-ups.”

The French commander seems to have suffered from what is known as an “idée fixe.” He was convinced that he knew what the Germans were going to do, and all evidence to the contrary was ignored.

As for French soldiers, though doomed by Gamelin’s inept leadership, their record was not that bad. Shortly after the fighting started, one or two French reservist divisions collapsed quickly under the fury of a combined arms assault, but man-for- man the French regulars were perhaps as effective as the Germans in 1940. The ground combat in Belgium is illustrative. During small unit encounters the French held their own. In the Battle of Hannut French tanks actually bested their German armored adversaries, but French tanks were mostly wasted elsewhere in penny packet tactics. Towards the end of May, in the siege of Lille, elements of the French 1st Army fought off two or three times their number of first-line German soldiers, including armored units, for several critical days, helping protect the Dunkirk perimeter and surrendering only after their ammunition was exhausted. Two years later, serving alongside the British in North Africa, outnumbered Free French troops battled units of the famed Afrika Korps to a standstill in the Battle of Bir Hakeim, leading Hitler to say, “After us, the French are the best soldiers in Europe.”

Unfortunately, at this moment in history, France had an incompetent in charge of its army. The Germans had an excellent, highly motivated military force commanded by brilliant tacticians. The French military had no real enthusiasm for the war, and some of its reserve units suffered from low morale. France may have lost the continental campaign even with a good general at the helm; but the Germans probably would have been severely bloodied, and the Allies could have held out in Britain, the Commonwealth, and French North Africa. Such an outcome might have ended Germany’s wars of conquest. As it was, at the end of June 1940 the German army stood unchallenged as the world’s strongest, swollen with the pride of victory and ready to obey the Fuhrer’s further commands.

Paris 1940