1850-1914

EUROPE STARTS ON THE PATH TOWARD DESTRUCTION

Europe had been totally transformed by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars. Following the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the continent entered an era during which armed conflicts were usually of limited scope and conducted by small, often professional armies. Total national involvement was rare. This all began to change with the rise of Prussia after 1850.

Europe 1850

In 1850 the Ottoman Empire still ruled over much of the Balkans, including the present-day states of Albania, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Macedonia, Romania, and parts of Greece.

The Austrian Empire dominated central Europe and contained territories that are now the present countries of Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Croatia, Slovenia. and parts of Poland, Italy, Romania and the Ukraine.

The Russia Empire was a vast colossus to the east, and it included the present-day states of Russia, Belorussia, the Baltic states, Finland, the Ukraine, and most of Poland. Most of its population was concentrated in the western part of the empire, and those areas to the east of the Ural Mountains remained largely a wilderness.

Enriched by its colonies in the Americas, Spain and the Spanish military had been a potent force in 16th century Europe, but after the mid-1600s Spain no longer played a major role in the continent’s power struggles.

France was the leading European land power from the time of Louis XIV until late-19th century, but any effort to expand its domains had been held in check by various combinations of other continental states, backed by the naval supremacy of Great Britain. That balance had been disrupted by the Napoleonic wars, but by 1815 France was back within its old borders, and Europe entered a period of relative peace.

With the exception of the Russian Empire, France was the most populous nation in Europe in 1815, but during the first half of the 19th century the French birth-rate experienced a gradual decline. By the late 1860s the North-German Confederation, Austro-Hungary and the United Kingdom all had growing populations that would soon exceed that of France.

France’s major continental rivals were Austria, Prussia, and the Russian Empire. In 1854-56 an alliance of France, Great Britain, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire defeated Russia in the Crimean War. Perhaps a half million Russian and Allied soldiers died during this bitter struggle, with disease being the primary killer. Three years later France and Sardinia went to war with Austria in the cause of Italian independence. The war ended with a French-Sardinian victory and creation of the Kingdom of Italy. Fewer than 40,000 Austrian, French and Sardinian soldiers died in this brief conflict.

In the meantime, Austria and Prussia were contending for leadership of the German states. Austria was larger and more populous, but its empire included many non-Germanic ethnicities, and its military lacked the cohesion of those of France and Prussia. As for the latter, Prussia was a highly militaristic state that Napoleon I had once described as being “hatched from a cannon ball.” Under the leadership of Frederick the Great it had vastly increased its territory, power and influence. Nevertheless, during the Napoleonic wars the French had repeatedly defeated and humiliated the Prussians. After the ignominy of that experience, Prussia reorganized its army, adopted universal military conscription, and created the General Staff.

Otto von Bismarck assumed a position of leadership in Prussia in 1862, and he worked to expand Prussia’s territory and position vis-à-vis the other German states. The army was once again reorganized and enlarged, and in 1866 it proved its military prowess by defeating the Austrian Empire along with a coalition including Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover and several smaller German states. The following year Prussia formed the North German Confederation, and Bismarck began looking for a way to unite all of Germany. He saw an opportunity to do this by persuading members of the Confederation to join Prussia in a war against France. By 1870 the Confederation had grown to include virtually all northern Germany plus south German states such as Bavaria. Of the major German states, only Austria remained outside the alliance.

In mid-July 1870, having been assured that the Confederation’s military forces were ready for action, Bismarck goaded France into a declaration of war. Though it had declared war, France was totally unprepared for hostilities. It had an excellent army composed of long-term soldiers, many experienced in colonial wars; but it could muster fewer than 400,000 men in the European theater, and it had no organized reserves. On the other hand, Prussia had universal military training, which meant a sizable standing army and plentiful trained reserves. Prussia alone could mobilize more than a million men, and the other German states contributed their share.

Battle of Gravelotte

The French field armies consisted of well-trained, well-equipped professionals, but they were outnumbered more than three to one. Also, whereas the French had not prepared for war, Bismarck had made certain that Prussia and its allies were poised to strike. While the French were still trying to assemble and organize their troops, the German armies rushed into eastern France and overwhelmed the French in a series of battles. By mid-August one of the two main French armies was trapped and besieged in the fortified city of Metz, and on September 1, 1870, the other army suffered a disastrous encirclement and defeat at Sedan. Napoleon III himself was captured, and the Second French Empire came to an end.

French patriots formed a new government, raised new armies, and fought on for another five months, but they sued for peace shortly following the fall of Paris on January 28, 1871. France was forced to pay a large war indemnity and lost the important provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, integral parts of France since the 17th century. Germany was now a united nation with the Prussian king as its emperor.

Most Europeans appeared surprised by the outcome, but many were pleased to see France receive its comeuppance. Unfortunately, French arrogance was soon replaced by more dangerous chest-thumping on the part of new German Empire.

Western Europe entered a golden age in the years following the Franco-Prussian War. The great nations of Europe were governed by civilized men, most of whom espoused Christian values, and many of the ruling families were related to one another. Peace and progress were watchwords of the day, and science and the arts flourished. There remained a great disparity in income and living conditions between the rich and the poor, and class distinctions remained somewhat rigid, but society appeared to be on its way to gradual improvement. Signs seemed positive almost everywhere, and there was a general sense of optimism about the future. Historians would later refer to this period as the “Belle Epoch.” Unfortunately, there was a deadly underlying menace that few people recognized. European leaders tended to glory in their nation’s military traditions, and many of those nations were armed to the teeth. Historian Barbara Tuckman used a haunting poetic image from Poe to describe these final years of the Belle Epoch. “From a proud tower in the town, Death looked gigantically down.”*

Let’s examine the state of Europe as it approached the coming cataclysm.

Germany had seen amazing progress. By 1910 the German population was 67 million and growing. German universities were the best in the world, German science was unequalled, and German factories were turning out high-quality products at ever-increasing rates. German workers were profiting from rudimentary social security and unemployment compensation programs. The future looked bright indeed.

France also prospered. It recovered quickly from the 1870-71 disaster. And even with its smaller, older, and somewhat static population of 40 million, the France of 1910 was still admired as the center of European fashion and culture. Agriculture remained the. dominant occupation, but French industrial output was not insignificant. Arts and letters flourished.

Britain was perhaps at the peak of its prestige and power. The British Isles were home to more than 45 million people, and the sun never set on the British Empire of 1910. From New Delhi to Cape Town, from Toronto to Sydney, ultimate allegiance was to the British monarch, and much wealth from these vast lands flowed into the imperial coffers or enriched British traders and merchants.

Eastern Europe was not as well off. Both Austro-Hungary and Russia were polyglot empires consisting of a variety of ethnicities with questionable allegiances. In Austro-Hungary, which was larger and more populous than France, a ruling class of Germans and Magyars sat upon a boiling cauldron of restive Slavs. Russia was also politically unstable and industrially backward. Despite its immense manpower resources, it had suffered a humiliating military defeat by Japan in 1905, and Russia’s huge underclass of recently freed serfs and disaffected ethnicities was restless.

With the accession of William II to the German throne in 1888, Europe slowly began trending toward confrontation and conflict. William was a grandson of Queen Victoria, long reigning British monarch. George V, King of Great Britain, was his uncle, and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia was his cousin. Unfortunately, William was somewhat unstable, and he had an inordinate love of the military. Soon he threw off the restraining influence of his old chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, and began putting his own somewhat bellicose imprint on the German military establishment and on German foreign policy. He sought to overawe Europe with his magnificent army, and he began building a navy that could potentially challenge the British. William was prone to frequent undiplomatic and provocative threats, and European prime ministers and ambassadors were often on tenterhooks. France and Russia signed a defensive alliance in response to the growing German menace. Britain was also alarmed, and it was moved to establish cordial relationships with France and Russia. It was apparent that the smallest spark could ignite a conflagration.

Europe 1914

By 1914 Germany was in in a state of total military readiness. Its industrial capacity, including arms production capability, eclipsed that of its European competitors. Universal military training provided it with a standing army of approximately 800,000, and there were 3.1 million trained reservists. Its forces were superbly equipped, and under the aegis of the German General Staff military strategy and tactics had been developed into virtual sciences. Senior staff officers had been preparing for a general European war for years, and many of them believed that the time was ready to strike. The army had never been better prepared, and its commanders were superbly confident. Realistic military exercises and maneuvers were used to prepare the troops for combat. The development and deployment of artillery and machine guns was a particular emphasis, and the German army had an impressive inventory of heavy caliber guns and the training to employ them effectively. There was much conversation within the German high command that it was time to finally dispose of their ancient enemy, the French. They knew that the French longed to revenge 1870 and take back Alsace-Lorraine. Never would Germany be better primed and ready to crush France once and for all.

France was also in a state of preparedness. After 1870 it instituted universal military training to match the Germans, and beginning in in 1913 France attempted to compensate for its smaller manpower pool by drafting men for three years of service rather than two. Thus, even with its smaller population, France managed to field a standing army nearly as large as that of Germany, though it had fewer reserves. The French army was of a high quality, but it was not as prepared for modern war as its enemy to the east. When the fighting started in 1914 the infantry was still attired in traditional blue coats and red trousers, beautiful targets for its camouflaged opponents. French war planning was relatively weak, and the army’s tactical doctrine and training were better suited to the 19th century. Infantry weapons were adequate, and the French had a very effective 75 mm field gun, but the German army had more than a three-to-one advantage in heavy guns such as high-angle howitzers and mortars. It is true that many Frenchmen wanted revenge for 1870. They bitterly resented the loss of Alsace-Lorraine. Nevertheless, most Frenchmen did not wish to start a war, and they looked anxiously at developments in Germany.

The British had no desire to become involved in a European land war, but the government had become alarmed by the growth of the German navy and William II’s increasingly bellicose comments. The United Kingdom, along with other major powers, had guaranteed Belgian neutrality, and there was concern that Germany might violate that state’s neutrality to attack France. British military service was voluntary. The nation possessed a large and powerful navy as required to protect its expansive empire, but the army was composed of a few superbly trained divisions of professional soldiers. British and French military staffs had discussed possible cooperative action should the Germans attack, but there was no formal alliance.

Austro-Hungary had a defensive alliance with Germany. Though more populous than France, its army was not as large and well-equipped. Nevertheless, it had a very bellicose commander who was eager for war against Serbia, his nation’s Slavic neighbor to the south. Many Austrians were convinced that Serbia was sowing seeds of discord among Austro-Hungary’s Slavic minorities (Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Bosnians, et. al.), and its military leaders wished for Serbia’s destruction.

Russia was the most populous country in Europe, twice that of Germany, and it was believed to have vast military potential. However, Russia armies had performed very badly in wars since the mid-19th century. They were poorly trained, poorly equipped, and often poorly led. Nevertheless, German leaders were concerned that Russia’s military strength appeared to be growing. As for Russia’s attitude, it was fearful of German aggression, firmly committed to the French alliance, and very resentful of Austrian treatment of its Slavic citizens and neighbors.

Because of the Franco-Russian alliance, Germany knew that if war came it would be a two-front war. France was considered the more dangerous enemy. Also, the large Russian army would be slow to mobilize. Therefore, in the event of hostilities, a smaller part of the German army along with Austro-Hungarian forces were expected to hold the Russians in check while the French were dealt with. Once France was out of the war, the Germans had no doubt of their ability to defeat the Russians. A quick victory in the west was critical.

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated by a Slavic nationalist. There was no conclusive evidence of Serbian state complicity, but Austrian militarists were determined to use this event to destroy Serbia, hotbed of the pan-Slavic movement. Austro-Hungarian leaders conferred with their German counterparts, and they were assured that Germany would provide full and unconditional support for any action they might choose to take. Upon receiving this assurance, Austro-Hungary prepared an ultimatum to Serbia. Serbia responded to the Austrian ultimatum politely and stated its willingness to cooperate in seeking out and prosecuting anyone involved in the assassination plot. The Austrian war party was not interested in Serbian cooperation. It was determined to destroy Serbia. They declared that the Serbian response was unsatisfactory, and Austria began to mobilize. As a fellow Slav state, Russia considered itself Serbia’s protector; and on July 31, 1914, following an Austro-Hungarian declaration of war against Serbia, Russia began to mobilize.

The German military high command was alarmed. Its war plan was based on the assumption that France must be defeated before Russia could fully mobilize. If the Russians were allowed to mobilize first it would throw their entire plan into disarray. Telegrams flew between the several European capitals in an effort to resolve the crisis, but it was to no avail. Austria was set on war against Serbia. and Russia was determined to protect the Serbs. General von Moltke, Chief of the German General Staff, believed it was the time to strike. At this point, Germany demanded that Russia cease its mobilization. When Russia refused, Germany initiated hostilities against both Russia and France. The Great War had begun.

Austria’s decision to destroy Serbia had been emboldened by German assurance of unconditional support, and any prospect of a peaceful resolution of the crisis fell victim to the inflexibility of Germany’s war plan. Europe thus descended into a cataclysmic orgy of self-destruction.

Berlin 1914, Marching off to War

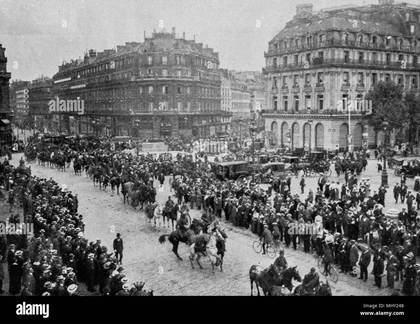

Paris 1914, The Call to Arms

The BEF Prepares to Embark