Introduction: Portions of this blog have been published before under different headings, but here I attempt to capture the whole history of the wars that shattered western civilization, beginning with the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and ending with the conclusion of World War II. Its a sad tale of arrogance, folly, devastation and bloodshed.

In the late 19th century Christendom appeared poised on the brink of an era of progress. Europe had been relatively peaceful following the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars in 1815, and there was a general spirit of progress and confidence. The horrors that soon followed turned hope and optimism into cynicism and despair. Couple that with the growing spirit of scientific materialism, and the west began to lose its spiritual roots. We are now adrift in a post-Christian world in which people are seeking for a sense of purpose and identity.

Read this and weep.

1850-1914

EUROPE STARTS ON THE PATH TOWARD DESTRUCTION

Europe had been totally transformed by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars. Following the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the continent entered an era when armed conflicts, though frequent, were usually of limited scope and conducted by small, often professional armies. Total national involvement was rare. This all changed with the rise of Prussia after 1850.

Europe 1850

In 1850 the Ottoman Empire still ruled over much of the Balkans, including the present-day states of Albania, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Macedonia, Romania, and much of Greece.

The Austrian Empire dominated central Europe and contained territories that are now the present countries of Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Croatia, Transylvania and parts of Poland.

The Russia Empire was a vast colossus to the east, and it and included the present-day states of Russia, Belorussia, the Baltic states, the Ukraine, and most of Poland. Most of its population was concentrated in the western part of the empire, and those areas to the east of the Ural mountains remained largely a wilderness.

With the exception of the Russian Empire, France was the most populous nation in Europe in 1800, but during the first half of the 19th century the French birth-rate experienced a gradual decline. By 1850 the North-German Confederation, Austro-Hungary and the United Kingdom all had growing populations that would soon exceed that of France.

Except for brief intervals, France was the leading European land power from the time of Louis XIV until mid-19th century. Its major rival was the highly militaristic Kingdom of Prussia. Napoleon I once remarked that Prussia had been hatched from a cannon ball. Nevertheless, under his leadership the French had defeated and humiliated the Prussians. After the ignominy of that experience Prussia reorganized its army and created the General Staff. In 1866 Prussia proved its military prowess by defeating the Austrian Empire along with a coalition including Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover and several smaller German states. The following year Prussia formed the North German Confederation, and Otto von Bismarck, Prussian Chancellor, began looking for a way to unite all of Germany. He saw an opportunity to do this by persuading members of the Confederation to join Prussia in a war against France. In mid-July 1870, having been assured that his military forces were prepared, Bismarck goaded France into a declaration of war.

Though it had declared war, France was totally unprepared for hostilities. It had a strong army composed of professional, long-term soldiers, many experienced in colonial wars, but it could muster less than 400,000 men and had no organized reserves. On the other hand, Prussia and some of the other German states had universal military training, which meant sizable standing armies and plentiful trained reserves.

Battle of Gravelotte

Prussia alone could mobilize more than three-quarters of a million men, and other German states contributed their share. The French field armies were therefore outnumbered more than three to one. Also, whereas the French had not prepared for this war, Bismarck had made certain that Prussia and the other Confederation members were poised to strike. The German armies rushed into eastern France and defeated the French in a series of battles, culminating in a disastrous encirclement and surrender of the last major French army at Sedan on September 1, where Napoleon III himself was captured.

The French formed a new government, raised new armies, and fought on desperately for another five months, but they sued for peace shortly following the fall of Paris on January 28, 1871. France was forced to pay a large war indemnity and lost the important provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, integral parts of France since the 17th century. Germany was now a united nation with the Prussian king as its emperor.

Most observers appeared surprised by the outcome, but many were pleased to see France finally receive its comeuppance. Unfortunately, French arrogance was soon replaced by more dangerous chest-thumping on the part of new German Empire.

Western Europe entered a golden age in the years following the Franco-Prussian War. The great nations of Europe were governed by civilized men, most of whom espoused Christian values, and many of the ruling families were related to one another. Peace and progress were watchwords of the day, and science and the arts flourished. There remained a great disparity in income and living conditions between the rich and the poor, but society appeared to be on its way to gradual improvement.

Germany in particular saw amazing progress. By 1910 the German population was 67 million and growing. German universities were the best in the world, German music was unequalled, and German factories were turning out high-quality products at an ever-increasing rate. There were the beginnings of social security and unemployment compensation. The future looked bright indeed.

France also prospered. It recovered quickly from the 1870-71 disaster. Even with its smaller, older, and somewhat static population of 40 million, the France of 1910 was still admired as the center of European fashion and culture. Agriculture remained the dominant occupation, but French industrial output was not insignificant. The arts and letters flourished.

Britain was perhaps at the peak of its prestige and power. The British isles were home to more than 45 million people, and the sun never set on the British Empire of 1910. From New Delhi to Cape Town, from Toronto to Sydney, ultimate allegiance was to the British monarch, and much wealth from these vast lands flowed into the imperial coffers or enriched British traders and merchants.

Eastern Europe was not as well off. Both Austro-Hungary and Russia were polyglot empires consisting of a variety of ethnicities with questionable allegiances. In Austro-Hungary, which was larger and more populous than France, a ruling class of Germans and Magyars sat upon a boiling cauldron of restive Slavs. Russia was also politically unstable and industrially backward. Despite its immense manpower resources, it had suffered a humiliating military defeat by Japan in 1905, and Russia’s huge underclass of serfs and disaffected ethnicities was restless.

Europe 1914

With the accession of William II to the German throne in 1888, Europe slowly began trending toward confrontation and conflict. William was a grandson of Queen Victoria, long reigning British monarch. George V, King of Great Britain, was his uncle, and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia was his cousin. Unfortunately, William was somewhat unstable, and he had an inordinate love of the military. Soon he threw off the restraining influence of his old chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, and began putting his own somewhat bellicose imprint on the German military establishment and on German foreign policy. He sought to overawe Europe with his magnificent army, and he began building a navy that could potentially challenge the British. William was also prone to frequent undiplomatic and provocative threats, and European prime ministers and ambassadors were often on tenterhooks. Britain was alarmed, and France and Russia were moved to sign a defensive alliance in response to the growing German threat. It was apparent that the smallest spark could ignite a conflagration.

In 1914 Germany was in in a state of total military readiness. Its industrial capacity, including arms production capability, eclipsed that of its European competitors. Universal military training provided it with a standing army of approximately 800,000, and there were 3.2 million trained reservists. Its forces were superbly equipped., and, under the aegis of the German General Staff, military strategy and tactics had been developed into virtual sciences. The Staff officers had been preparing for a general European war for years, and many of them believed that the time was ready to strike. The army had never been better prepared, and its commanders were superbly confident. Realistic military exercises and maneuvers had been used to ready the troops for combat. The development and deployment of artillery and machine guns was a particular emphasis, and the German army had an impressive inventory of heavy caliber guns and the training to employ them effectively. There was much thought among senior leaders that it was time to finally dispose of their ancient enemy, the French. They knew that the French longed to revenge 1870 and take back Alsace-Lorraine. Never would Germany be better primed and ready to crush France once and for all.

France, Germany’s age-old foe, was also in a state of preparedness. Even with its smaller population, France managed to field a standing army nearly as large as that of Germany, though it had fewer reserves. Beginning in in 1913, France attempted to compensate for its smaller manpower pool by drafting men for three years of service rather than two. The French army was of a high quality, but it was not as ready for modern war as its enemy to the east. When the fighting started in 1914 the infantry was still attired in traditional blue coats and red trousers, beautiful targets for its camouflaged opponents. French war planning was relatively weak, and the army’s tactical doctrine and training were better suited to the 19th century. Infantry weapons were adequate, and the French had a very effective 75 mm field gun, but the German army had more than a three-to-one advantage in heavy guns such as high-angle howitzers and mortars. It is true that many Frenchmen wanted revenge for 1870. They bitterly resented the loss of Alsace-Lorraine. Nevertheless, most Frenchmen did not wish to start a war, and they looked anxiously at developments in Germany.

The British had no desire to become involved in a European land war, but they had become alarmed by the growth of the German navy and William II’s increasingly bellicose comments. The United Kingdom, along with other major powers, had guaranteed Belgian neutrality and were concerned that Germany might violate that state’s neutrality to attack France. Britain had a large navy but only a few superb divisions of professional soldiers. British and French military staffs had discussed possible cooperative action, but there was no formal alliance.

Austro-Hungary had a defensive alliance with Germany. It had a population of 52.3 million, and Its standing army was 420,000, with a ready reserve of 0,000 men. The army’s chief weakness lay in the multitude of ethnicities and languages. Most of its officers were Austrian, and the language of command was German, but Slavs composed almost 50 per cent of the army’s rank and file. The Austrian war party, led by Chief of Staff Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf, was eager for war against Serbia. They were convinced that Serbia was sowing seeds of discord among Austro-Hungary’s Slavic minorities (Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Bosnians, et. al.), and were determined to finally eliminate that threat.

Russia was the most populous country in Europe, twice that of Germany. Though Russia had vast military manpower potential, its armies had performed very badly in wars since the mid-19th century. They were poorly trained, poorly equipped, and often poorly led. Russian leaders were firmly committed to the French alliance and very resentful of Austrian treatment of its Slavic citizens and neighbors.

Because of the Franco-Russian alliance, Germany realized that if war broke out it would be a two-front war. France was considered the most dangerous enemy. Russia had large army, but it would be slow to mobilize. If war came, a smaller part of the German army and Austro-Hungarian forces were expected to hold the Russians in check while the French were dealt with. Once France was out of the war, the Germans had no doubt of their ability to defeat the Russians. A quick victory in the west was critical.

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated by a Slavic nationalist. Though there was no direct evidence of Serbian state complicity, Austrian militarists were determined to use this event to destroy Serbia, hotbed of the pan-Slavic movement. Austro-Hungarian leaders conferred with their German counterparts, and they were assured that Germany would provide full and unconditional support for any action they might choose to take. Upon receiving this assurance, Austro-Hungary began preparations for war. On July 23, 1914, almost four weeeks after the assassination, Austria delivered an ultimatum to Serbia. Serbia responded to the Austrian ultimatum amicably and stated its willingness to cooperate in seeking out and prosecuting anyone involved in the assassination plot. The Austrian war party was not interested in Serbian cooperation. It was determined to destroy Serbia. The Serbian response was rejected, and Austria began to mobilize. As a fellow Slav state, Russia considered itself Serbia’s protector; and on July 31, 1914, following an Austro-Hungarian declaration of war against Serbia, Russia began to mobilize.

The German military high command was alarmed. Its war plan was based on the assumption that France must be defeated before Russia could fully mobilize. If the Russians were allowed to mobilize first it would throw their entire plan into disarray. Telegrams flew between the several European capitals in an effort to resolve the crisis, but it was to no avail. Austria was set on war against Serbia. and Russia was determined to protect the Serbs. At this point Germany demanded that Russia cease its mobilization. When Russia refused, Germany initiated hostilities against both Russia and France . The Great War had begun.

Austria’s decision to destroy Serbia had been emboldened by German assurance of unconditional support, and any prospect of a peaceful resolution of the crisis fell victim to the inflexibility of Germany’s war plan. Europe thus descended into a cataclysmic orgy of self-destruction.

1914

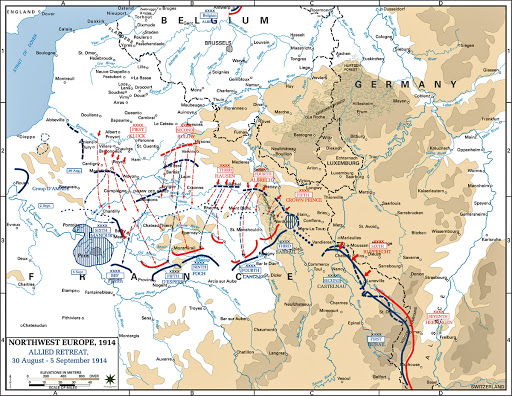

THE SCHLIEFFEN PLAN

On the afternoon of August 3, 1914, two days after declaring war on Russia, Germany declared war on France and began implementing a long-held strategy conceived by the former chief of staff of the German army, Alfred von Schlieffen, This strategy was calculated to achieve the total defeat of France in six weeks. To accomplish this objective, Schlieffen’s plan had been refined through field exercises carried out over a period of many years. As the British feared, the German’s intended to attack France through neutral Belgium. Since the French-German frontier was well defended, the General Staff saw this as the only path to a speedy victory. The German plan thus called for a massive sweep through Belgium into northeastern France aimed at trapping and destroying major French forces against the German border. German leaders realized that invading Belgium might bring Britain into the war on France’s side, but that was a relatively minor concern. The British could only field an army of about 120,000 troops, an insignificant number as compared to the massive German and French armies facing each other along the frontiers.

Germany’s annual class of recruits numbered approximately 400,000 men, and five of these classes were activated as the regular field army, nearly 2,000,000 men including the professional cadre. There were another 3,000,000 in the general reserve. The usual practice was to use these reserves to replace losses among the regulars; but in defiance of normal conventions the German military had organized 400,000 of these older reservists into 20 or more divisions and mixed them in with the regulars. This gave German commanders even greater confidence that they would be able to overwhelm French resistance. Only eleven German divisions (about 250,000 men) were stationed on the Eastern Front, where they, along with the Austro-Hungarian Army, were expected to hold the slow-mobilizing Russians in check while the western campaign was concluded. Approximately 2,150,000 German soldiers were available for the western thrust.

French recruitment classes numbered about 250,000 men, and when fully mobilized the regular army was almost 1,250,000 strong, with another 2,000,000 men being in the general reserve. Metropolitan France received some additional manpower support from French North African colonials and African native units, but their contribution was very limited during the war’s early stages. Whereas the Germans increased the size of its armies by immediately incorporating older reserves among its active combatants, the French initially rejected that idea and were not aware that Germans had done so. As a result, the sweep through Belgium was much stronger than the French commander thought possible, while the Germans continued to maintain powerful units along the French-German border.

Upon mobilization, German divisions quickly moved toward the Belgian/French frontiers, with the far heavier concentration being in the north. On August 4 they marched into Belgium. That small nation was able to field a army of about 130,000 men to face them. The Belgians fought bravely but were overwhelmed by the massive German onslaught. Ninety percent of Belgium was overrun by the third week of August, but remnants of the Belgian army continued to hold a small slice of land near the English Channel till war’s end. It played a very small role in the overall campaign; but Germany’s invasion of Belgium did cause Britain to enter the war, and the small but superbly trained British army, initially 100,000 strong, was deployed in northeastern France by mid-August.

The seven German armies were numbered from north to south, with the German First Army on the extreme right. Opposing them, the five French armies were numbered from the south. The French Fifth Army, farthest north, was flanked on its left by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). They faced the German First and Second Armies and much of the Third.

Opening Moves

The Germans charged into Belgium on August 4 and swept rapidly toward the southwest. Little more than two weeks later elements of the German First, Second and Third Armies began to encounter BEF and French Fifth Army units not far from the French frontier. The Allied forces were badly outnumbered and in danger of being overwhelmed. Desperate fighting occurred at places like Mons, Charleroi and Le Cateau, and the French in particular suffered very heavy casualties. French infantry doctrine of 1914, “attaque a outrance”, emphasized the necessity to attack in virtually all circumstances, and it led to horrendous losses of men. French dead and wounded in many early engagements was more than twice that of their enemy. German superiority in heavy artillery and machine guns was particularly devastating.

Attaque a Outrance

Within days the BEF and the French Fifth Army were in rapid retreat toward Paris. It was not, however, a rout. The retreating soldiers retained unit cohesion, and they turned at times to counterattack the pursuing, Germans. For example, on August 29 the French Fifth Army turned and gave a sharp check to the German Second Army near St. Quentin. The following day the Fifth resumed its retreat.

South of the northern battle French generals pursued the pre-war plan to take the war into Germany. That meant an advance into Alsace-Lorraine, France’s lost provinces. Within days of war’s outbreak French First Army troops charged into Alsace and captured Mulhouse. The French paraded through the town and were welcomed by many of its citizens. The Germans then counterattacked, and the city exchanged hands several times before the French established a defensive line on high ground to the west, leaving Mulhouse in German hands. French offensive operations in this area were soon curtailed by the transfer of troops to bolster hard-pressed units in front of Paris. The Alsace region was best suited for defensive warfare, and the sector remained relatively quiet for the remainder of the war.

The French March into Mulhouse

The French suffered bitter repulses in the Ardennes region and further south in Lorraine. Marshal Joffre, the French Commander in Chief, had based his war strategy on hopes of a breakthrough in the German center. This breakthrough was to be achieved by the Fourth Army attacking through the Ardennes and the Second and Third Armies advancing east of Nancy. He was aware of the probable German thrust through Belgium, but he grossly underestimated its strength and believed that the French Fifth Army could contain it. He also thought the German’s Belgian sweep would weaken their center and expose them to a counterpunch. Since the Germans were employing many reserves as first-line troops, Joffre was wrong on both counts. The BEF and the French Fifth Army were badly outnumbered in the north, and attacking French troops did not outnumber defenders in the south.

The Fourth Army contained some of the very best divisions in the French army, and its commanders had high hopes for the success of its attack. But determination and bravery were not enough. Poor French tactics were pitted against superbly trained German infantry units that were supported by an overwhelming advantage in machine guns and medium/heavy artillery. Entire divisions and regiments literally ceased to exist. To illustrate, the elite French Third Colonial Division suffered about 10,500 casualties, lost its commander and both brigade commanders, and was effectively destroyed as a fighting force. The entire French Fourth Army reeled to the rear in some disarray and was pushed back into France.

East of the city of Nancy the French Second and Third Armies attacked the German Sixth and Fifth. Again, contrary to Joffre’s estimates, the forces opposing the French were equal or superior in numbers. The Germans were also in prepared positions and poised for action. German artillery fire was murderous, and that alone accounted for perhaps 75% of French casualties. It was a near disaster for French arms. The French infantry was repulsed everywhere and fell back toward Nancy. The Kaiser came to the front anticipating a triumphal march into that French city, but his arrival proved premature. The French were now in defensible positions, and they were learning from experience. The Germans were now the attackers, and they were repeatedly thrown back. By the second week of September the fighting line in this area was stabilized near the frontier. Both sides had sustained horrendous losses.

German Artillery

All along the front the French had been repulsed. Casualty figures were almost incomprehensible. On one day alone, August 22, 1914, an estimated 27,000 French soldiers died in battle and another 70,000 or more were wounded – almost 100,000 casualties in a single day; and similar bloodletting went on up and down the line from mid-August into September. By September 3 more than a quarter of the French soldiers that started the war were either dead or hors de combat. In the north the BEF along with the French Fifth, Fourth and Third Armies were retreating. Elsewhere the French armies were binding their wounds and holding on. Reserve units were being called up and thrown into battle. The situation was desperate, but Marshal Joffre still had hope. How could he snatch victory from defeat?

The German army had not escaped unscathed. Though not so severe as French casualties, German units had also suffered heavy losses; and early in the campaign General von Moltke, Chief of the German General Staff, weakened his offensive thrust by transferring two Army corps (about 120,000 men) to the Eastern Front to help counter a Russian incursion into East Prussia. To add to German problems, their supply lines were lengthening while those of the French compressed. Lines of communication required defending and strong points needed garrisoning, therefore the advancing armies front line troops began to thin out.

Taking advantage of his interior lines, Marshal Joffre began transferring units from his right to the left. Two new French armies were formed, the Sixth Army on the extreme left, and the Ninth Army between the Fourth and the Fifth. By transferring units from his First and Second Armies and calling up reserves, Joffre removed the numerical imbalance on his left flank.

On September 3 the four armies of the advancing German right wing stretched along a line from Verdun to Amiens. Their First Army was within 30 miles of Paris, and on that day the French government announced its relocation to Bordeaux. The BEF had retreated so far south that it was almost out of the fight.

On the Eve of the Marne

To many observers the situation appeared hopeless, but Joffre continued to exhibit an air of calm confidence. At this critical moment, a French reconnaissance flight revealed that the German First Army had started a southeastward wheel north of Paris in an apparent effort to trap and destroy the French Fifth Army. When Marshal Joffre saw that the German First Army was turning toward the southeast, he realized that the enemy’s own right flank was exposed. It was time for a counterstroke.

French and British troops were exhausted by their long retreat in the blazing August heat, but the German’s were just as fatigued by the seemingly endless marches in pursuit. Though they had been defeated all up and down the line, the French infantry was beginning to improve its tactics. There is no military school like combat, and French officers and men had experienced graduate level instruction from some true professionals. The doctrine of “attaque a outrance” was gradually abandoned in favor of a more judicious use of cover and entrenchment. As for the BEF, its commander had virtually given up the battle as lost, but Joffre finally persuaded him to join a counteroffensive. Both British and French soldiers had experienced a surfeit of retreating and reacted positively when the French commander-in-chief gave his order to turn and fight.

On the eve of battle, Marshall Joffre issued the following communique to his troops:

“At the moment when the battle upon which hangs the fate of France is about to begin, all must remember that the time for looking back is past; every effort must be concentrated on attacking and throwing the enemy back….Under present conditions no weakness can be tolerated.”

Receiving Joffre’s order, the Allied divisions stopped their retreat and turned northeast to face the foe. On September 6, they attacked. The entire German line was overextended, and gaps had appeared between some of the advancing armies. The French Fifth Army moved quickly into the gap between the German First and Second Armies, with the BEF following. On the German extreme right, the newly formed French Sixth Army struck the German First. The fighting there was fierce, and it appeared that the Sixth Army might be overcome, but critical French reinforcements arrived during the evening of September 7 (including the famous taxicab army), and the Sixth held its ground. Late the following day the French Fifth Army launched an attack against the German Second, further widening the gap in the German lines. The Second was being pressed by the Fifth on its right and the new French Ninth Army on its left, creating some danger of encirclement. The German high command became seriously alarmed over the deteriorating situation; and unlike the ever-cool Joffre, General von Moltke, the German commander, began to show signs of a nervous collapse. On September 9 the German First, Second and Third armies were ordered to retreat and regroup.

The retreating armies were pursued by the French and British, and the Allied despair of September 3rd was replaced by thoughts of victory. However, the pace of their advance was too slow to force continued German retirement, and the Germans stopped their retreat after falling back about 40 miles to a point north of the Aisne River. There they dug in on high ground and prepared trenches. As it developed, there was no regrouping and resumption of the offensive. The German retreat between September 9 and September 13 marked the abandonment of the Schlieffen Plan and all hope of a quick victory in the west.

Hundreds of thousands of young men were already dead or wounded, and the slaughter had only just begun. Four more bitter years of war were to follow, then came what amounted to a twenty-year truce. In 1939 it all began again. Western Civilization has never fully recovered from these self-inflicted wounds. The day that marks the beginning of World War 1 should be a day of mourning for all mankind.

French Soldiers at the Marne

(Note the blue coats, red trousers, and no helmets)

1914-1939

WINNING THE WAR, LOSING THE PEACE

After the Battle of the Marne ended on September 9, 1914, the Allied and German armies attempted to outflank each other. Failing this, they entrenched and faced off over a no-man’s land. The trenches stretched from the Swiss alps to the English Channel. From time to time each side attempted to break the other’s line, but all attempts ended in bloody failure.

In the meanwhile, in the east, a war of movement was taking place. The Russians invaded eastern Prussia in late August 1914, but by September 15 the invaders had been defeated and thrown back into Russia with heavy losses. Over the next two years the Germans and Austro-Hungarians fought the Russians back and forth on the Eastern Front. The Germans constantly shifted troops from west to east and back in response to changing situations. Austro-Hungarian armies were hard pressed and often defeated. On the other hand, German armies, well equipped and brilliantly led, continually outmatched their Russian opponents and drove them slowly eastward. During this time, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire entered the war on Germany’ s side. Italy and Romania joined the Allies.

In early 1917, in the third year of the Great War, fighting on the western front was at a stalemate. Two things then occurred to change the course of history. First, on February 1 Germany decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare in the hope of knocking the United Kingdom out of the war. That decision helped cause the United States to enter the war on Germany on April 4. Second, revolution erupted in St. Petersburg on March 8, and Russian armies were no longer a serious threat. Over the next eight months Russia gradually exited the conflict, and Germany began shifting its eastern units to the western front.

The Germans had realized that resuming unrestricted submarine warfare might bring the United States into the war, but the American army was small, inexperienced, and totally unprepared for European warfare. The Germans believed that the war would be over long before the United States could make any impact. Nevertheless, on the assumption that the United States would become involved, Arthur Zimmermann, the German Foreign Secretary, sent a telegram to Mexico in January 1917 proposing a German-Mexican alliance against the United States. This telegram was exposed, and that revelation, coupled with Germany’s renewed submarine campaign, propelled America to declare war.

The Zimmermann Telegram Exposed

The following fourteen months saw a desperate race between Germany and the Allies. The German army, bolstered by arrival of its eastern divisions, sought to deliver a knock-out blow in France. General Erich Ludendorff, a brilliant tactician, was now the German field commander. Beginning in March 1918, and employing new and effective tactics, he unleashed a series of offensives that gradually pushed the Allies back to the old Marne battleground. Meanwhile, America was training and equipping troops to succor the Allies. By June and July of 1918 these new arrivals were beginning to make a difference. The Allies also benefitted from a recently established unified command under the direction of the highly capable French Marshal Ferdinand Foch. The Germans were defeated in the Second Battle of the Marne in July. That ended the last major German offensive operation of the war. Beginning in August, Foch coordinated a series of attacks that drove the Germans steadily eastward

Meanwhile, there was increasing pressure on other fronts. Greece had entered the war on the Allied side, and in September 1918 a multinational army under the command of French General Franchet d’Esperey struck north from Macedonia. Germany’s ally Bulgaria was soon out of the war, and by late October Allied troops were penetrating deep into Hungary. The Austro-Hungarian Empire sued for peace on November 3. A few days earlier, Turkey, another German ally, had also dropped out of the fight. Germany now stood alone.

In late September the German high command advised the civilian government that the situation was hopeless. Germany extended peace feelers, but there was haggling over details. In the meantime, the German situation continued to deteriorate. Parts of the country were suffering severe food shortages because of the British naval blockade, and in early November riots broke out in Kiel and other cities. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated on November 9, after which Germany agreed to an armistice on Allied terms. The guns stopped firing on November 11, 1918.

ARMISTICE

Western civilization had been badly shaken. More than twenty million soldiers and civilians lay dead from the war, and maimed victims could be seen everywhere. It appeared that an entire generation of young men had been sacrificed to the god of war. And now Europe and America were experiencing the effects of a virulent influenza pandemic that killed millions more. In many Europeans, faith and optimism had been replaced by cynicism and despair.

The collapse of the German army in late 1918, following so soon after high hopes of victory, was a profound shock to the German people. The Versailles Treaty was a humiliation. Germany was blamed for the war, forced to pay heavy reparations, returned Alsace-Lorraine to France, forfeited its colonies, and lost significant territory to a reestablished Polish state. Germany’s principal ally, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was totally dismembered.

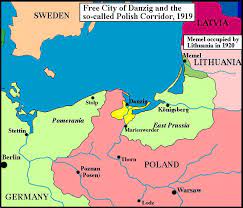

German agitators propagated the false narrative that the army was not defeated but had been stabbed in the back by the civil government. There were cries for revenge and the recovery of lost German territory. The Polish corridor separating East Prussia from the rest of Germany was a particular sore point.

The Polish Corridor

As the Great War ended, many French military leaders were convinced that Germany simply wished to resume the war under more favorable circumstances. They wanted to march all the way to Berlin to make the German people taste the totality of defeat. Instead, the German Rhineland area was only temporarily occupied, and, except for limited forays by French troops into Alsace-Lorraine, Germany had not experienced any Allied incursions during the hostilities.

France emerged from the conflict shaken to its core. Some of the richest areas in the land had been devastated, and roughly half of French males of military age had been killed or wounded. Germany had also suffered grievous casualties, but the German homeland and infrastructure remained mostly untouched. Germany had a strong industrial base and a young, growing population. The French population was older and relatively static, and France could never reverse its growing manpower deficit.

The war had destroyed the British professional army and inflicted heavy losses on its levies of conscripts, a new experience for the island kingdom. The casualty rate among men of the British upper class, provider of its officer corps, was especially severe. The nation was sickened by the carnage and firmly set against involvement in any future continental conflict.

Regardless of strong anti-war sentiments, the French did not trust the Germans and continued to remain armed and vigilant. A considerable part of France’s national budget was dedicated to defense. France spent more on the military than any other country until Germany itself began rearming in 1933, and this huge investment continued despite onset of the economic depression. The army was maintained at a high level, and a large portion of the defense budget was spent on the Maginot Line. Unfortunately, the French air arm did not receive equal attention.

Maginot Line Cupulas

During the financial and political turmoil that swept the world in the 1920s and 1930s, vicious, godless men clawed their way into positions of power. Benito Mussolini gradually assumed leadership in Italy, Josef Stalin rose to the top in the Soviet Union, and militarists seized the government in Japan. Lastly, in Germany, there appeared the worst of them all – Adolf Hitler. These evil men were consumed with a thirst for power and conquest.

Following the 1918 Armistice and the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations had been established to help maintain world peace. Although the United States refused to join, it was hoped that the other great powers, acting in concert, could settle future disputes between nations equitably and peaceably. Unfortunately, the plan did not work. The first real test came in 1931, when the Japanese invaded Manchuria. After much delay, the League demanded that the Japanese leave Manchuria. Instead, the Japanese left the League of Nations. No one was willing to go to war over the issue, so nothing was done. This pattern was repeated when the Italians invaded Ethiopia in 1935. The League again proved itself to be totally ineffective. The German Fuhrer took note.

Immediately upon taking the reins of power in 1933, Hitler set his face toward war and began rebuilding Germany’s military arsenal. Alarmed by the Nazi leader’s bellicose fulminations and Germany’s growing military strength, the French realized that conflict was probably inevitable and might be coming relatively soon.

Though supporting large military expenditures, French leaders abhorred the thought of another European war, and they were determined to do all in their power to avert conflict. If war should come, however, French strategic thinking gravitated around defense. The French high command was acutely aware of the devastating casualties caused by their predecessors’ offensive tactics in 1914, and they were predisposed to rely primarily on defensive strategy and tactics in any future conflict. The “attaque a outrance” spirit that had motivated French officers and men in 1914 had almost entirely dissipated. One might say, with some truth, that the Great War had taken the starch out of the French. This was also true of the British. Only the German military, motivated by a thirst for revenge and mesmerized by the flaming rhetoric of Hitler, was primed for aggressive, risk-taking warfare.

The first concern of French leaders was to ensure that the British entered any coming war on their side. The French knew that it would be almost impossible to stand up to Germany alone. The Great War had caused another sharp dip in the French birth rate, and German males of military age now numbered twice those of the French. Also, German industrial production was second only to that of the United States, far more than that of France. The threat to France was formidable. At the same time, the French government was weakened by deep political divisions, and these fissures affected both civil and military efficiency. Political parties rotated in and out of office frequently. Most of the Great War heroes were now dead, and there was no strong civilian leader nor outstanding military commander in whom the people had confidence. Many civil and military officials were pessimistic about the overall situation.

Tensions between France and Germany rose steadily through the 1930s as Germany violated terms of the Versailles Peace Treaty and began a full-scale rearmament program. In March 1936 the Germans marched into the demilitarized Rhineland in clear violation of the Versailles Treaty. France and Britain did not respond. Later in 1936 both Germany and Italy inserted themselves into the Spanish Civil War, supporting General Franco as he led a rebellion against the socialist led republican government. The Soviet Union aided the republicans. Britain and France decided not to become involved. The new German military, especially its air force, received valuable experience.

In early 1938 Germany annexed Austria, making it part of the Greater German Reich. Hitler then made obvious his desire for further German territorial expansion, and the newly established states of Czechoslovakia and Poland (created in part out of Germany and the old Austro-Hungarian Empire following the Great War) were particularly vulnerable because of the large numbers of ethnic Germans in each country. Hitler began pressing for the annexation of certain areas of both these nations.

Sudetenland

In October 1938, the crisis came to a boiling point when Hitler indicated that he was prepared to take German speaking areas of Czechoslovakia (the Sudetenland) by force. He threatened war unless the Czechs gave in. France had a mutual defense pact with the Czechs, and the two nations appeared ready to face up to the German threat. The British feared that they would be drawn into the possible conflict. Europe was on the brink of another explosion. A hurried conference was called, and the leaders of Britain, France, Germany, and Italy met in Munich to seek a solution.

As the heads of state met in Munich, Hitler appeared ready to march into Czechoslovakia; but many German army commanders believed that they were not yet prepared for war. Some of them were plotting to overthrow Hitler should he order them to attack. They feared that a combination of French, British, and Czech arms would be impossible to overcome; also, the Soviet Union might become involved. Unfortunately, the Allies were not aware of dissension in the German ranks. Even so, Daladier, the French Premier, wished to confront Hitler at this moment; but Prime Minister Chamberlain of Britain was horrified by the prospect of another war. Also, his military advisors insisted that Britain was not ready for conflict. They feared the possibility of an all-out German aerial assault and insisted on more time to build British air defenses. Chamberlain therefore chose to accept Hitler’s assurances of peace if he got the Sudetenland. Hitler also promised that he would make no more territorial demands. Daladier was not willing to fight without British support, so he gave in. Czechoslovakia was forced to surrender critical areas of the country to the Germans, and Chamberlain returned home to London proclaiming, “Peace in our time!” Daladier had no such illusions.

Hitler’s leadership position was now unassailable. In a few short years he had reoccupied the Rhineland, absorbed Austria into the greater German Reich, and taken significant areas of Czechoslovakia, rendering that nation virtually defenseless. All this had been accomplished without firing a shot. It seemed that the Fuhrer could do no wrong. The German populace and the military were now fully behind him.

Less than six months after the Czechoslovakian accords of October 1938, Hitler violated the Munich agreements and occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia. Even Chamberlain the peacemaker was now convinced that war was inevitable. There would be no more concessions. When Hitler began pressuring Poland for territory, Britain and France signed guarantees of mutual protection with that nation.

Unfortunately for the Allies, their earlier abandonment of Czechoslovakia had a profound effect on the attitude of the Soviet Union. Prior to that time the Soviets had been inclined to support France and Britain against Germany, especially if it threatened Poland. A German occupied Poland would become the Soviet’s neighbor, and Hitler had made no secret of his hatred for the communist state and his desire for German lebensraum (living space) in Belorussia and the Ukraine. Following the Allies’ pusillanimous betrayal of Czechoslovakia, however, the Soviets changed their approach. They now decided to stand aside in the hope that Germany and the western democracies would destroy each other, leaving the Soviet Union “cock of the walk” in Europe. In accordance with this new thinking, Stalin and Hitler signed a mutual non-aggression treaty in late August 1939 that included a secret clause calling for a division of Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union. With Soviet neutrality assured, Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, and World War II began.

1939-1940

BLITZKRIEG

French Soldiers on Parade, 1939

Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, and, true to their treaty obligations, Britain and France declared war on Germany. However, neither nation did much to help their Polish ally. With the Germany army heavily engaged in Poland, the French could have launched an attack from the east. Instead, the French high command remained totally wedded to its defensive strategy. The Poles fought valiantly, but by the end of September the country was virtually out of the war and divided between occupying forces from Germany and the Soviet Union. This division was in accordance with a secret clause in the German-Soviet non-aggression pact. The Germans then began transferring their troops to the western front, and Hitler urged his generals to rush preparations for an attack on France. For various reasons, however, the attack was delayed until May 1940.

For seven months following the fall of Poland there was a period known to journalists as the sitzkreig or Phony War. The Germans and Allies stared at each other across no-man’s land. Hitler made some peace overtures, but the Allies would not accept so long as Poland was occupied. And why trust Hitler to keep any promises? Therefore, the British and French simply awaited developments and tried to prepare for an expected onslaught.

While waiting, the Allies engaged in a very timorous sort of warfare. A few bombing raids were conducted against German military installations, and there were some limited naval operations, but otherwise things remained quiet. In fear of reprisals, British bombers dropped propaganda leaflets on German cities rather than bombs. The Luftwaffe had acquired a fearsome reputation during the Spansh civil war, and residents of London and Paris were very concerned about the possibility of German bombing raids. In truth, neither Briton nor Frenchman had his heart in this new conflict.

In April 1940, the Germans surprised the Allies with a quick strike north at Denmark and Norway. The Allies attempted to respond but were generally unsuccessful. Denmark was overwhelmed in a matter of hours, and the Norwegian campaign ended in early June 1940 with that nation’s complete occupation.

On May 10, 1940, the Germans finally attacked in the west. The sudden and complete collapse of France that followed was a shock to the entire world. German victory was not that unpredictable, but the speed and totality of it was a surprise to everyone, including the Germans. It remains an irradicable stain on French arms.

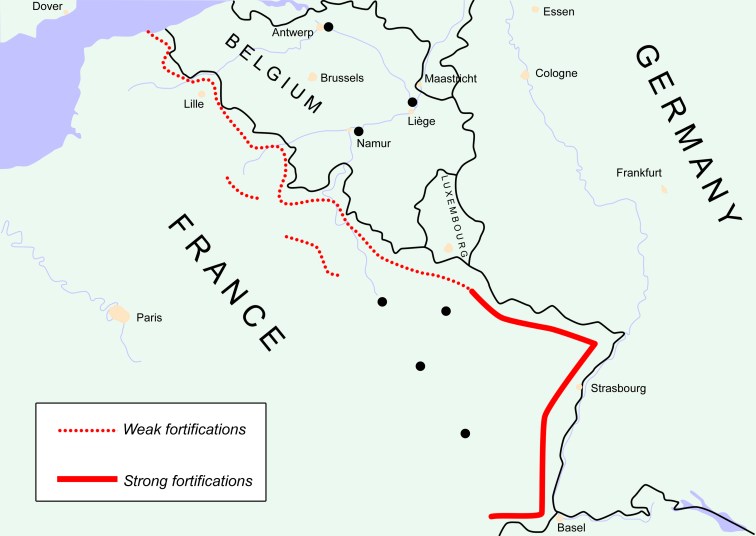

When the war began in September 1939 the French Army was believed by many to be the best in the world. Germany had a far stronger air force, but wars still must be fought out on the ground, and many observers thought the French might have an advantage in that area. France also had the Maginot Line, a massive series of fortifications along the French-German boundary.

Marshal Maurice Gamelin, who had achieved some distinction as a French staff officer in World War I, was serving as the overall Allied military leader, and he had developed detailed plans to be put into operation once the Germans resumed their offense in the spring of 1940.

No one could be certain where the enemy would strike, but Gamelin was convinced that the Maginot Line would effectively deter any German assault along the Franco-German border. Marshal Gamelin’s confidence in the line was not misplaced. In the years since World War 2 there has been a tendency to disparage fixed fortifications, but the Maginot Line was truly impressive. Heavy, well protected guns had been sited to give covering fire to other strongpoints, and infantry units were placed behind the line for counterattacks in the event the enemy attempted a penetration in force. Unfortunately, Gamelin deployed a full 45 French infantry divisions in support of the Maginot Line, an excessive number considering the strength of the fortifications. Only 14 German divisions were facing them; and, as things developed, the Germans never made any serious attack in this area until the battle was virtually over and supporting infantry had been withdrawn. Another 9 French divisions were stationed along the Franco-Italian border. This number proved to be more than adequate when the Italians entered the war and attacked France on June 10. The French threw them back with no difficulty, but by then the war was lost.

The Maginot Line

With the Franco-German and Franco-Italian borders secure, Gamelin expected that the Germans would charge at France through Belgium much as they had done in 1914. This time German offensive plans also involved the Netherlands, but that had little impact on the overall campaign.

French fortifications were much less formidable along the Belgian and Luxembourg borders north of the Maginot Line. This area was not suited for deep fortifications; but more to the point, Gamelin’s plans called for Allied units to advance and confront the Germans in central Belgium and prevent their incursion into France. The German army had occupied and devastated northeastern France during World War I, and the French were determined to avoid a repeat.

By tapping its manpower resources to the fullest, France managed to field 109 army divisions. With 54 French divisions deployed along the German and Italian borders, 55 were available for the decisive struggle in the north. Only 24 of these French divisions deployed in the main battle area were well-equipped, first-class fighting units, another 10 were second class reserve divisions of mixed quality and 21 divisions composed the general reserve (older reservists). Alongside the French were the 11 first-class divisions of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and 20 Belgian divisions. The Dutch could field 10 divisions, but they were poorly equipped and out of the fight within a few days. Facing the Allied troops in the north would be the 135 divisions of the Wehrmacht, minus those 14 divisions along the Franco-German border. This gave the Germans a 121 to 86 divisional advantage in the critical zone. Perhaps 40 of the German divisions could be considered fully equipped, first-class units, another 36 second class, and 45 were in their general reserve. The allies would be outnumbered in this area, but these were not impossible odds for soldiers in strong defensive positions. The moment German forces violated the Dutch and Belgian frontiers, Gamelin planned to send his strongest and most mobile formations forward to take up defensive positions along the Dyle River in central Belgium. He was confident that French troops, allied with the British and Belgians, could hold off the German onslaught on that narrow front.

The Dyle Line

Along with the Germans, the French had the most experienced and battle-ready troops on the continent, and overall, the French were perhaps better equipped. Many senior officers and NCOs in both armies had served in the Great War and were tactically proficient. The British Expeditionary Force consisted of more than 350,000 men It was well trained and led, but it was a small force when compared to the size of the French and German armies; and this was even though the United Kingdom’s population was slightly larger than that of France in 1940. The British were slow to realize that they were in a life-or-death struggle. The 20 division Belgian army consisted of a few first-class fighting units along with reserve formations of questionable quality.

The greatest German advantage was in their offensive spirit, which was enhanced among frontline soldiers by the heavy use of methamphetamines. The German military pioneered the use of performance enhancing drugs Also, they developed a new battlefield tactic that involved combining large, armored formations with infantry and air support to achieve breakthroughs. The Germans had some valuable practice with these tactics in Poland.

The French had more tanks than the Germans, but they were widely dispersed among infantry units in a support role. At the urging of armor enthusiasts like Charles De Gaulle, the French had formed four armored divisions. These units were only recently organized and entirely untested. The ten German panzer divisions had been hardened in the Polish campaign. Therefore, as the new battle began on the western front, the Germans had a significant edge over the French and British in organizational structure and in their appreciation for the effect of fast-moving tank formations supported by infantry and combined with incessant air attacks. This new tactic was referred to by journalists as blitzkrieg or lightening war.

Following the German charge into Holland and Belgium on May 10, the French and British units along the Belgian border moved north to link arms with their new allies. There had been no military pre-planning with the Belgians. Belgium had scrupulously maintained a posture of neutrality and did not wish to give Hitler any excuse to draw them into the war. Of course, Hitler needed no excuse, and because of the lack of coordination, there was considerable confusion as British and French troops moved into position alongside the Belgians on the Dyle. The German juggernaut quickly charged through the Netherlands and northern Belgium and struck the Allies before they had a chance to fully deploy.

As the battle began the Allied and German forces were situated as follows. The BEF (11 divisions), French 1st Army (10 divisions), and French 7th Army (7 divisions) were moving north to join the Belgians. The 7th even raced into the Netherlands to help the Dutch, but the Dutch quickly capitulated, and the 7th retired south toward the Dyle. Holland’s rapid exit from the war was prompted by the German air force’s massive bombing of Rotterdam and threats of more such raids to come. There were heavy civilian casualties, and the Dutch ran up the white flag to avoid more useless slaughter.

Meanwhile, the German 6th Army (19 divisions) and 18th Army (11 divisions) were charging southeast to attack the Allies in Belgium. Gamelin positioned the French 9th Army (9 divisions) and the French 2nd Army (8 divisions) to the right of the BEF and French 1st Army on the Dyle. The purpose of these other armies was to protect the 1st Army’s flank and provide a link to units along the Maginot Line. The southernmost units of the 9th Army and all divisions of the 2nd were situated to the immediate west and south of the Ardennes, a heavily forested area of southeastern Belgium that the French commander believed to be entirely unsuited for mechanized operations. Gamelin realized that the Germans might send infantry through the Ardennes, but he believed the passage of major armored units and heavy artillery through that difficult terrain was practically impossible. He sent no major French units into the Ardennes, and units assigned to the 9th and 2nd Armies and posted to on the edges of the forest were chosen based on his conviction that it was extremely unlikely they would become heavily engaged in the fighting. A number of these divisions were reservist organizations of questionable quality and poorly equipped with antiaircraft and antitank guns. Gamelin assumed that if these troops should come under heavy attack by German infantry, reinforcements could be moved up in time to provide necessary support.

By May 12th Allied and German forces were fully engaged in central Belgium along the Dyle River line. The results were mixed. The Germans were the aggressors, but the Allies were holding their own. In fact, French tanks performed better than German armor in the Battle of Hannut, and Allied troops repulsed German infantry attacks all along the front. All seemed to be going as Gamelin had planned. The next day, however, a mailed fist struck French armies on their right.

Large German units, including armored formations, managed to rapidly push their way through the Belgian Ardennes area virtually uncontested, and on May 13th they confronted elements of the 2nd and 9th French Armies along the Meuse River. The speed of the attack was jaw-dropping. High on methamphetamines, German tank drivers covered ground night and day,

Breakthrough

almost without stopping. French commanders were caught entirely off guard and failed to respond with the necessary alacrity. The French regular units fought well, but the poorly prepared reservist divisions were extremely vulnerable. Woefully underequipped with antitank and antiaircraft guns, one or two of these divisions broke under the attacks of German armor and infantry combined with relentless bombing by German aircraft. German air support took the role of heavy artillery, and the fearsome Stuka dive bombers were particularly effective against unprotected infantry. A hole was punched in the French line, and German tank units raced toward the French coast

The German left wing now swinging into northern France comprised the bulk of the German Army’s offensive power. It consisted of the 4th, 12th, and 16th German Armies plus Panzer Groups Kleist and Guderian, a total of 46 divisions, including 9 panzer (tank) divisions. The Germans had another 45 divisions, lower quality units, in their general reserve.

On May 15th the rapidly advancing German left faced the remnants of the French 2nd and 9th Armies along with French reserve formations totaling another 21 divisions. These reserve units were badly situated, mostly unmotorized, and unable to respond quickly to the growing crisis.

Winston Churchill had succeeded Chamberlain as British Prime Minister on May 10th, the very first day of the German offensive. On May 15th Premier Reynaud contacted Churchill and told him that the battle was lost. The news seemed unbelievable. The British leader flew to Paris on May 16th and pressed Marshal Gamelin for a counterattack, but Gamelin informed him that he had no mobile reserve. Churchill was shocked by this statement as well as the general air of defeatism that seemed to infect the French high command. Almost all French mobile formations had been rushed into Belgium on the first day of battle, and they were now in danger of being cut off in the north. The only remedy was to attempt a breakout and try to regroup.

Marshal Gamelin was dismissed on May 19th and succeeded by General Maxime Weygand, a capable commander; but the change in command did not immediately improve the overall situation. Weygand had to be recalled from Syria, and the inevitable delays arising from switching generals disrupted Allied plans for a counteroffensive and breakout. Two or three critical days were lost during the change of leaders, and in the meantime the situation had become even more difficult.

On May 20th German armored units reached the English Channel, severing supply lines to the Allied armies in Belgium, more than a million men. These armies contained the best and most mobile British and French formations. They continued to fight the Germans to their north and east while facing increasing pressure from the south. With lines of communication completely severed, the Allied units began to experience shortages of food and supplies, including essential ammunition and fuel. There were several abortive attempts to break the encirclement, but all failed. The Belgians’ fought alongside the British and French until surrendering on May 28th. The situation was desperate for the remaining Allied forces, and they had already begun retiring toward the Channel ports in hope of evacuation. Then came the Miracle of Dunkirk. Over the period May 27 through June 3 over 339,000 British and French troops were transported from Dunkirk to Britain, saving them from certain destruction or capitulation. All their tanks, artillery, and trucks were abandoned along with perhaps 900,000 Allied prisoners of war (Brench, British, and Belgian) from various parts of the collapsing front. Some British and French units fought courageously and brilliantly in defense of the Dunkirk perimeter, but the overall campaign could only be labeled as a total Allied disaster,

The Germans then regrouped their armies in northern France for the final thrust. They now had far better than a two-to-one divisional advantage, and the French had lost almost all their mobile, armored units. The outcome was not long in doubt. Weygand organized the defense skillfully, and the French fought desperately. Within a few days, however, panzer units managed to bypass French strong points and break into open country. On June 10th Italy joined the war on Germany’s side, declaring war against both France and Britain. On June 14th the Germans entered Paris. On June 22nd the French capitulated.

Following World War II there has been a tendency to criticize the French nation for its rapid collapse and to disparage the quality and bravery of French fighting men. Indeed, the French military has become the butt of jokes.

Certainly, the French decision to surrender on June 22nd, 1940, can be censured. France and Britain had promised each other not to make a separate peace. After the collapse in the north, Paul Renaud, Charles de Gaulle and some others wished to continue the war from North Africa, but the defeatists took charge and sued for an end to hostilities. It was not France’s finest hour, and the new French government was little more than a lackey to its German masters, bringing even more shame to the French nation.

As France surrendered, there were some British leaders who also wished to negotiate with Hitler, but Churchill stood firm. At this critical moment in its history France needed a leader with the stature and grit of a Churchill. Unfortunately, no such man was available. De Gaulle had the grit but not the stature. He was only a colonel when the war began.

As for the French military, though its army was doomed by Gamelin’s miserable performance, its record was not that bad. One or two reservist divisions collapsed quickly under the fury of the combined arms assault, but man for man the French regulars were perhaps as effective as the Germans in 1940. The fighting in Belgium is illustrative. During small unit encounters the French held their own. In the Battle of Hannut French tanks actually bested their German armored adversaries, but French tanks were wasted elsewhere in penny-packet tactics. Later, in the siege of Lille, elements of the French 1st Army fought off two or three times their number of first-line German soldiers, including armored units, for several critical days, thus helping protect the Dunkirk perimeter and surrendering only after their ammunition was exhausted. In the summer of 1942, serving alongside the British in North Africa, outnumbered Free French troops battled units of the famed Afrika Korps to a standstill in the Battle of Bir Hakeim, leading Hitler to say “After us, the French are the best soldiers in Europe.”

Gamelin’s poor placement of Allied troops contributed much to the debacle in 1940. Prior to battle he should have moved many of the men backing the Maginot Line north to the critical front; and the French 7th Army, instead of racing into Holland, would have been much better employed as support to the French armies on the Meuse. As for the Ardennes, a few well equipped divisions could have rushed into that critical area and blocked the German thrust through that difficult and highly defensible terrain. Instead, despite intelligence warnings, Gamelin assumed the Germans could not move armor through such a heavily forested area and sent no troops to prevent such a passage. That proves the old adage that “assumption is the mother of foul-ups.”

Unfortunately, at this moment in history, France had an incompetent in charge of its army. The Germans had an excellent, highly motivated military force commanded by brilliant tacticians. The British and French were reluctant warriors. France may have lost the continental campaign even with a good general at the helm, but the Germans probably would have been severely bloodied; and the Allies could have held out in Britain, the Commonwealth, and French North Africa. Such an outcome might have ended Germany’s wars of conquest. As it was, at the end of June 1940 the German army stood unchallenged as the world’s strongest, swollen with the pride of victory and ready to obey the Fuhrer’s further commands.

Paris 1940

1940-1945

THE WORLD IN FLAMES

With the fall of France in June 1940, Britain stood alone against Germany and Italy. The British army was in a state of total disarray. It was never very large, and it had lost almost all its equipment during the evacuation from Dunkirk. The imminent threat of invasion loomed over the British Isles as the Germans assembled landing boats on the shores of the English Channel. On the other side of the Atlantic, America was in a state of shock. The sudden collapse of France was completely unexpected and frightening. What if the Germans managed to defeat the British and took over the British fleet? How could the United States survive in a world dominated by totalitarian states? Sentiment in the country was generally pro-Allied, but most Americans did not wish to become involved in a shooting war. Neutrality remained the watchword. Nevertheless, President Franklin Roosevelt was determined to do everything he possibly could to see that Britain withstood the coming assault. Substantial materiel support was provided to Britain, stretching our neutrality laws to the limit. Also, in preparation for possible future troubles, the United States instituted its first peacetime military draft. The American armed forces had a long way to go. In June 1940 the United States Army was smaller than those of several third-class European states.

Two things deterred the German invasion of Britain. First was the British air force. Second was the British navy. Hitler and his generals determined that their initial task was to destroy the British air force by a series of concentrated attacks on the enemy’s air bases. Once the Royal Air Force’s fighting effectiveness was destroyed, it might be possible for the Luftwaffe to provide the air cover needed to push an invasion force through the British fleet. Unfortunately for Hitler, the RAF did not cooperate. Although Chamberlain’s kowtowing to Hitler at Munich in October 1939 may have cost the Allies a chance to thwart the Fuhrer’s plans at that time, the intervening months had given the British time to develop their air defenses. By June 1940 they had a chain of interconnected radar towers backed by a powerful fleet of modern fighter planes. All through the summer and early autumn of 1940, British and German pilots fought it out over the skies of England and the channel, and, in the end, the Germans lost the contest. German plane losses were too heavy, and British air power, though wounded, remained strong.

Battle of Britain

In Churchill’s eloquent words of tribute to British airmen, “Never has so much been owed by so many to so few.” The Luftwaffe then switched its major effort from attacking RAF air bases to the terror bombing of British cities, and German invasion plans were put on indefinite hold. After the threat of invasion eased Churchill could afford to be jocular. Speaking to the Canadian Parliament in late 1941, he said: “After France fell, General Weygand (the French commander) said that the Germans would wring the neck of the British chicken.” Pause. “Some chicken!” Another pause. “Some neck!”

Elsewhere the war continued to spread. On November 30, 1939, Soviet troops had invaded Finland. The Finns resisted skillfully and with great courage, and over the winter months the Soviet forces were thrown back again and again. Finally, the sheer weight of numbers and equipment took its toll, and Finland was forced to sue for peace in March 1940. To German observers of the Russo-Finnish war, it appeared that Soviet military leaders were totally incompetent and their soldiers ill-prepared for conflict.

The Winter War

In June 1940 the Soviets occupied the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania and parts of Romania. In Africa, the Italians took over British Somaliland in August and attacked Egypt in September. On October 28, 1940, the Italians invaded Greece from their occupied state of Albania.

Italian war efforts were fated for nothing but frustration. Their thrust into Greece was turned back, and soon hard fighting Greek troops advanced deep into Albania. In Africa, the British repulsed the Italian advance into Egypt and pursued their beaten foe into Libya. The Italians were also defeated in British Somaliland, and the British then attacked Italian forces in Ethiopia. Mussolini’s quest for military glory and a restoration of Roman power had been a total failure. At that point it was up to Germany to succor its ally. In March 1941, General Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps landed in Libya, and the combined German-Italian force soon began pushing the British back toward Egypt. In April, on the other side of the Mediterranean, German, Italian, and Romanian armies swept down from the north and overwhelmed Yugoslav and Greek resistance. Yugoslavia and Greece surrendered in late April, and the strategic island of Crete fell by the end of May. The British dispatched troops to Greece in a forlorn effort to help, but this doomed expedition only served to cost men and equipment and weaken British forces in North Africa.

On June 22, 1941, the Germans turned their armed might against their erstwhile friend, the Soviet Union. The German-Soviet non-aggression pact of 1939 had been nothing but an expedient sham. As Hitler revealed in Mein Kampf, always his intention had been to strike east in the quest for lebensraum. Churchill’s reaction to this latest turn of events was interesting. He promised to give the Soviets all possible assistance. When reminded of his long-standing condemnation of communism and the Soviet Union, he said (paraphrasing) that “If Hitler’s armies invaded Hell he would have a few kind words of support for the Devil.” British materiel support was necessarily limited, but the United States slowly began sending what was one day to become a steady stream of war supplies to the Soviets.

The Murmansk Run

Although the British had warned Stalin about the impending German assault, Stalin refused to believe the warnings, and the Soviet army and air force were caught by surprise. As a result, initial losses were devastating. Soviet planes were destroyed on the ground, and hundreds of thousands of their soldiers were killed, captured, or sent reeling to the rear. Based on initial progress, Hitler and his generals believed that the war would be over long before Christmas. But Soviet resistance stiffened, and the terrain became more difficult. Even so, by early December 1941, the Kremlin was in view of the forward German units. For the Germans, however, as it was for the French under Napoleon in 1812, a frigid enemy was waiting. General Winter entered the fray, and the German attack ground to a halt. Moscow did not fall, and the Soviets even mounted a successful counterattack. Further north, the Germans besieged the great city of Leningrad. Perhaps as many as a million soldiers and civilians in that city starved to death or were killed by air attacks and bombardment, but the city would not surrender. Meanwhile, behind German lines, special Nazi paramilitary units were secretly beginning their systematic effort to exterminate Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian Jews.

Suddenly a new and dangerous foe appeared in the Pacific.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese naval aviators, flying from aircraft carriers, attacked the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor. A few days later, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, and America was now fully engaged in World War II. It is one of the great puzzles of the war that Hitler was so foolish as to declare war on the United States without insisting that the Japanese join him in the fight against the Soviet Union. The German army was at the gates of Moscow in early December 1941, and a Japanese attack from the east could have made a great difference. Germany was not obligated to join Japan in the war against America. Their treaty with Japan required them to become involved only if Japan was attacked. In this instance, it was Japan that did the attacking, and Germany could have stayed out of it. Nevertheless, Churchill was delighted with Hitler’s decision to stand with his Asian ally. His fervent prayers that America join Britain in the fight against Germany had finally been answered affirmatively, and he felt assured of final victory.

Pearl Harbor

The Japanese attack was not unexpected. It was only the place of the attack that surprised the American military. American-Japanese relations had been steadily deteriorating since Japan invaded mainland China in 1937. Citizens of the United States were horrified by reports of Japanese atrocities in China – the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians, the mass rapes, the use of Chinese prisoners of war for bayonet practice, the frequent decapitations, etc. The government of the United States became alarmed as the Japanese evinced even greater territorial ambitions, and it began putting increasing pressure on Japan to pull back. The pressure was applied in a series of economic sanctions, and with the imposition of an American oil embargo the matter was brought to a head. Without oil, the Japanese army and navy would be severely handicapped, and territorial expansion would no longer be possible. Plenteous oil could be had in the Netherlands East Indies, but the American Pacific Fleet must be neutralized to make it possible to take this oil. The Japanese military leaders hoped that a severe bloody nose would dissuade the United States from further interference in the Far East, an area in which they believed Americans had few legitimate interests and should rightly regard as in Japan’s sphere of control. Out of this thinking came the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Pearl Harbor was a remarkable victory for Japanese naval aviation but a disaster for the Japanese nation. The sneak attack aroused the rage of the American people, and nothing would assuage their anger but the total defeat of the Empire of Japan. At the outbreak of war, the navy was the best prepared and the most professional of all the American military services, but the fleet was hit hard at Pearl Harbor and seriously outgunned in the Pacific for many months thereafter. Also, the Japanese had the advantage of battle experienced soldiers and airmen and, at least initially, better aircraft. They also had superb torpedoes that wreaked havoc on Allied ships during the early naval engagements. The first six months of war in the Pacific theater were a near calamity for the Allies. American outposts in Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines all fell during that time, along with Hong Kong, British Malaysia (including the great naval base at Singapore), and the Dutch East Indies. The Philippine affair was particularly painful to Americans as their beleaguered forces made their brave but futile stands in Bataan and on Corregidor. The defenders suffered from disease and near starvation, and there was no way to reach them with relief. The fall of Singapore was perhaps an even more painful experience for the British. That bastion of empire and symbol of British power had been considered virtually impregnable, yet it had surrendered to a numerically inferior enemy after a very short siege. The British Empire was shaken to its core. It seemed that the Japanese could not be stopped.

The Fall of Singapore

With their impressive display of military might and acumen, the Japanese achieved revenge on those foolish and arrogant Caucasians who thought of Asians as an inferior human species. While exacting their vengeance, Japanese soldiers frequently engaged in acts of brutality seldom exceeded in the long and lamentable history of man’s cruelty to man. Furthermore, these quick conquests bred a feeling of overconfidence, or what the Japanese later referred to as “victory disease.” The antidote was on its way.

In early June 1942, heroic American naval aviators achieved their first great victory over the Japanese in what later became known as the “Miracle of Midway”. In April, Japanese pride had been pricked by an air raid on Tokyo and other Japanese cities. The raid did little damage but was psychologically devastating. The attack had been carried out by bombers launched from the deck of an American carrier; therefore, Japanese military leaders determined that they must eliminate the few remaining American carriers in the Pacific. To achieve this goal, the Japanese naval command devised an elaborate plan calculated to lure the American fleet out to certain destruction. The bait was to be placed by an attack on the Midway Islands, a small atoll located approximately 1300 miles northwest of Hawaii. The Japanese thought that the Americans would respond by sending their fleet from Pearl Harbor to succor the island defenders, thus falling into a Japanese trap. Unknown to the Japanese, however, American cryptanalysts had achieved a degree of success in cracking Japanese naval codes, and Pacific Fleet Headquarters in Hawaii was alerted to the planned Midway operation. When the Japanese fleet arrived off Midway, American forces were positioned to surprise them.

Midway