(Sequel to “Europe Starts on the Path to Self-Destruction”)

On the afternoon of August 3, 1914, two days after declaring war on Russia, Germany declared war on France and began implementing a long-held strategy conceived by the former chief of staff of the German army, Alfred von Schlieffen.

Germany’s offensive thrust to the east was calculated to achieve total defeat of France in six weeks. To accomplish this objective, Schlieffen’s plan had been refined through field exercises carried out over a period of many years. As the British feared, the German’s intended to attack France through neutral Belgium. Since the German-French frontier was well defended, the General Staff saw this as the only path to speedy victory. The German plan therefore called for a massive sweep through Belgium into northeastern France aimed at enveloping Paris and trapping major French forces against the German border. German leaders realized that invading Belgium might bring Britain into the war on France’s side, but that was a relatively minor concern. The British could only field an army of about 120,000 troops, an insignificant force as compared to the massive German and French armies facing each other along the frontiers.

Germany’s annual class of recruits numbered approximately 400,000 men, and five of these classes were activated as the regular field army, nearly 2,000,000 men including the professional cadre. There were another 3,000,000 in the general reserve. The usual practice was to use these reserves to replace losses among the regulars; but in defiance of normal conventions the German military had organized 400,000 of these older reservists into 20 or more divisions and mixed them in with the regulars. This gave German commanders even greater confidence that they would be able to overwhelm French resistance. Only eleven German divisions (about 250,000 men) were stationed on the Eastern Front, where they, along with the Austro-Hungarian Army, were expected to hold the slow-mobilizing Russians in check while the western campaign was concluded. Approximately 2,150,000 German soldiers were available for the western thrust.

French recruitment classes numbered about 250,000 men, and when fully mobilized the regular army was almost 1,250,000 strong, with another 2,000,000 men being in the general reserve. Metropolitan France received some additional manpower support from French North African colonials and African native units, but their contribution was very limited during the war’s early stages. Whereas the Germans increased the size of its armies by incorporating older reserves among its active combatants, the French initially rejected that idea and were not aware that Germans had done so. As a result, the sweep through Belgium was much stronger than the French thought possible, while the Germans continued to maintain powerful units along the French-German border.

Upon mobilization, German divisions quickly moved toward the Belgian/French frontiers, with the far heavier concentration being in the north. On August 4 they marched into Belgium. That small nation was able to field a army of about 130,000 men to face them. The Belgians fought bravely but were overwhelmed by the massive German onslaught. Ninety percent of Belgium was overrun by the third week of August, but remnants of the Belgian army continued to hold a small slice of land near the English Channel till war’s end. It played a very small role in the overall campaign; but Germany’s invasion of Belgium did cause Britain to enter the war, and the small but superbly trained British army, initially 100,000 strong, was deployed in northeastern France by mid-August.

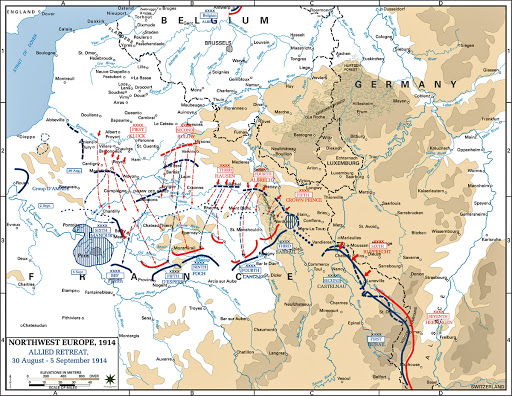

The seven German armies were numbered from north to south, with the German First Army on the extreme right. Opposing them, the five French armies were numbered from the south. The French Fifth Army, farthest north, was flanked on its left by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). They faced the German First and Second Armies and much of the Third.

OPENING MOVES

The Germans charged into Belgium on August 4 and swept rapidly toward the southwest. Little more than two weeks later elements of the German First, Second and Third Armies began to encounter BEF and French Fifth Army units not far from the French frontier. The Allied forces were badly outnumbered and in danger of being overwhelmed. Desperate fighting occurred at places like Mons, Charleroi and Le Cateau, and the French in particular suffered very heavy casualties. French infantry doctrine of 1914, “attaque a outrance”, emphasized the necessity to attack in virtually all circumstances, and it led to horrendous losses of men. French dead and wounded in many early engagements was more than twice that of their enemy. German superiority in heavy artillery and machine guns was particularly devastating. Within days the BEF and the French Fifth Army were in rapid retreat toward Paris. It was not, however, a rout. The retreating soldiers retained unit cohesion, and they turned at times to counterattack the pursuing Germans. For example, on August 29 the French Fifth Army turned and gave a sharp check to the German Second near St. Quentin. The following day the Fifth resumed its retreat.

South of the northern battle French generals pursued their pre-war plan to take the war into Germany. That meant an advance into Alsace-Lorraine, France’s lost provinces. Within days of war’s outbreak French First Army troops charged into Alsace and captured Mulhouse. The Germans counterattacked, and the city exchanged hands several times before the French established a defensive line on high ground to the west, leaving Mulhouse in German hands. French offensive operations there were soon curtailed by the transfer of troops to bolster hard-pressed units in front of Paris. The Alsace region was best suited for defensive warfare, and the sector remained relatively quiet for the remainder of the war.

The French suffered bitter repulses in the Ardennes region and further south in Lorraine. Marshal Joffre, the French Commander in Chief, had based his war strategy on hopes of a breakthrough in the German center. This breakthrough was to be achieved by the Fourth Army attacking through the Ardennes and the Second and Third Armies advancing east of Nancy. He was aware of the probable German thrust through Belgium, but he grossly underestimated its strength and believed that the French Fifth Army could contain it. He also thought the German’s Belgian sweep would weaken their center and expose them to a counterpunch. Since the Germans were employing many reserves as first-line troops, Joffre was wrong on both counts. The BEF and the French Fifth Army were badly outnumbered in the north, and attacking French troops did not outnumber defenders in the south.

The Fourth Army contained some of the very best divisions in the French army, and its commanders had high hopes for the success of its attack. But determination and bravery were not enough. Poor French tactics were pitted against superbly trained German infantry units that were supported by an overwhelming advantage in machine guns and medium/heavy artillery. Entire divisions and regiments literally ceased to exist. For example, the elite French Third Colonial Division suffered about 10,500 casualties, lost its commander and both brigade commanders, and was effectively destroyed as a fighting force. The entire French Fourth Army reeled to the rear in some disarray and was pushed back into France.

East of the city of Nancy the French Second and Third Armies attacked the German Sixth and Fifth. Again, contrary to Joffre’s estimates, the forces opposing the French were equal or superior in numbers. The Germans were also in prepared positions and poised for action. German artillery fire was murderous, and that alone accounted for perhaps 75% of French casualties. It was a near disaster for French arms. The French infantry was repulsed everywhere and fell back toward Nancy. The Kaiser came to the front anticipating a triumphal march into that French city, but his arrival proved premature. The French were now in defensible positions, and they were learning from experience. The Germans were now the attackers, and they were repeatedly thrown back. By the second week of September the fighting line in this area was stabilized near the frontier. Both sides had sustained horrendous losses.

All along the front the French had been repulsed. Casualty figures were almost incomprehensible. On one day alone, August 22, 1914, an estimated 27,000 French soldiers died in battle and another 70,000 or more were wounded – almost 100,000 casualties in a single day; and similar bloodletting went on up and down the line from mid-August into September. By September 3 more than a quarter of the French soldiers that started the war were either dead or hors de combat. In the north the BEF along with the French Fifth, Fourth and Third Armies were retreating. Elsewhere the French armies were binding their wounds and holding on. Reserve units were being called up and thrown into battle. The situation was desperate, but Marshal Joffre still had hope. How could he snatch victory from defeat?

The German army had not escaped unscathed. Though not so severe as French casualties, German units had also suffered heavy losses; and early in the campaign General von Moltke, Chief of the German General Staff, weakened his offensive thrust by transferring two Army corps (about 120,000 men) to the Eastern Front to help counter a Russian incursion into East Prussia. To add to German problems, their supply lines were lengthening while those of the French compressed. Lines of communication required defending and strong points needed garrisoning, therefore the advancing armies front line troops began to thin out.

Taking advantage of his interior lines, Marshal Joffre began transferring units from his right to the left. Two new French armies were formed, the Sixth Army on the extreme left, and the Ninth Army between the Fourth and the Fifth. By transferring units from his First and Second Armies and calling up reserves, Joffre had removed the numerical imbalance on his left flank.

On the Eve of the Marne

On September 3 the four armies of the advancing German right wing stretched along a line from Verdun to Amiens. Their First Army was within 30 miles of Paris, and on that day the French government announced its relocation to Bordeaux. The BEF had retreated so far south that it was virtually out of the fight. To many observers the situation appeared hopeless, but Joffre continued to exhibit an air of calm confidence. At this critical moment, a French reconnaissance flight revealed that the German First Army had started a southeastward wheel north of Paris in an apparent effort to trap and destroy the French Fifth Army. When Marshal Joffre saw that the German First Army was turning toward the southeast, he realized that the enemy’s own right flank was exposed. It was time for a counterstroke.

French and British troops on the left were exhausted by their long retreat in the blazing August heat, but the German’s were just as tired by seemingly endless marches in pursuit. Though they had been defeated all up and down the line, the French infantry was beginning to improve its tactics. There is no military school like combat, and French officers and men had experienced graduate level instruction from some true professionals. The doctrine of “attaque a outrance” was abandoned in favor of a more judicious use of cover and entrenchment. As for the BEF, its commander had virtually given up the battle as lost, but Joffre finally persuaded him to join a counteroffensive. Both British and French soldiers had experienced a surfeit of retreating and reacted positively when the French commander-in-chief gave his order to turn and fight.

On the eve of battle, Marshall Joffre issued the following communique to his troops:

“At the moment when the battle upon which hangs the fate of France is about to begin, all must remember that the time for looking back is past; every effort must be concentrated on attacking and throwing the enemy back….Under present conditions no weakness can be tolerated.”

Receiving Joffre’s order, the Allied divisions stopped their retreat and turned northeast to face the foe. On September 6, they attacked. The entire German line was overextended, and gaps had appeared between some of the advancing armies. The French Fifth Army moved quickly into the gap between the German First and Second Armies, with the BEF following. On the German extreme right, the newly formed French Sixth Army struck the German First. The fighting there was fierce, and it appeared that the Sixth Army might be overcome, but critical French reinforcements arrived during the evening of September 7 (including the famous taxicab army), and the Sixth held its ground. Late the following day the French Fifth Army launched an attack against the German Second, further widening the gap in the German lines. The Second was being pressed by the Fifth on its right and the new French Ninth Army on its left, creating some danger of encirclement. The German high command became seriously alarmed over the deteriorating situation; and unlike the ever-cool Joffre, General von Moltke, the German commander, began to show signs of a nervous collapse. On September 9 the German First, Second and Third armies were ordered to retreat and regroup.

The retreating armies were pursued by the French and British, and the Allied despair of September 3rd was replaced by thoughts of victory. However, the pace of their advance was too slow to force continued German retirement, and the Germans stopped their retreat after falling back about 40 miles to a point north of the Aisne River. There they dug in on high ground and prepared trenches. As it developed, there was no regrouping and resumption of the offensive. The German retreat between September 9 and September 13 marked the abandonment of the Schlieffen Plan and all hope of a quick victory in the west.

French Soldiers at the Marne

(Note the blue coats, red trousers, and no helmets)

Hundreds of thousands of young men were already dead or wounded, and the slaughter had only just begun. Four more bitter years of war were to follow, then came what amounted to a twenty-year truce. In 1939 it all began again. Western Civilization has never fully recovered from these self-inflicted wounds. The day that marks the beginning of World War 1 should be a day of mourning for all mankind.